Chapter 7

The Great Depression and World War II

As the United States stood on the verge of World War II, African Americans continued to suffer discrimination. Relegated to low-paying jobs and segregated conditions, they remained targets of intimidation and violence. Black sharecroppers lost their livelihoods to larger agricultural operations and modern farm machinery. Though progress was made through President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, many African Americans still wanted change.

Serving in World War II

African American troops arrive in England

African Americans served in segregated units throughout World War II. Most served in support units—driving trucks, maintaining equipment, and delivering supplies. As casualties mounted, African Americans saw combat in Europe and the Pacific.

Women also served in segregated units in the Women’s Army Corps and the Army Nurse Corps. Black nurses were only allowed to aid African American troops and German prisoners. Most Black servicemembers resented segregated units, but more than 900,000 served and many earned wartime honors.

Army Chaplain Louis J. Beasley

Chaplain Louis J. Beasley

Chaplain kit used by Army Chaplain Louis J. Beasley

Louis J. Beasley was one of the highest-ranking African American chaplains during World War II. He ministered to the segregated 92nd Division, and his work included moral and spiritual counseling, organizing social activities, and acting as a liaison between Black troops and their white officers. As Beasley described it, “my job in this Division is to keep these white folks and Negroes apart, in order that I can keep them together.” Beasley was awarded the Purple Heart and the Bronze Star for his heroics near the battlefield.

World War II soldiers from Company D, 8th Battalion, Ft. Belvoir, Virginia, 1942

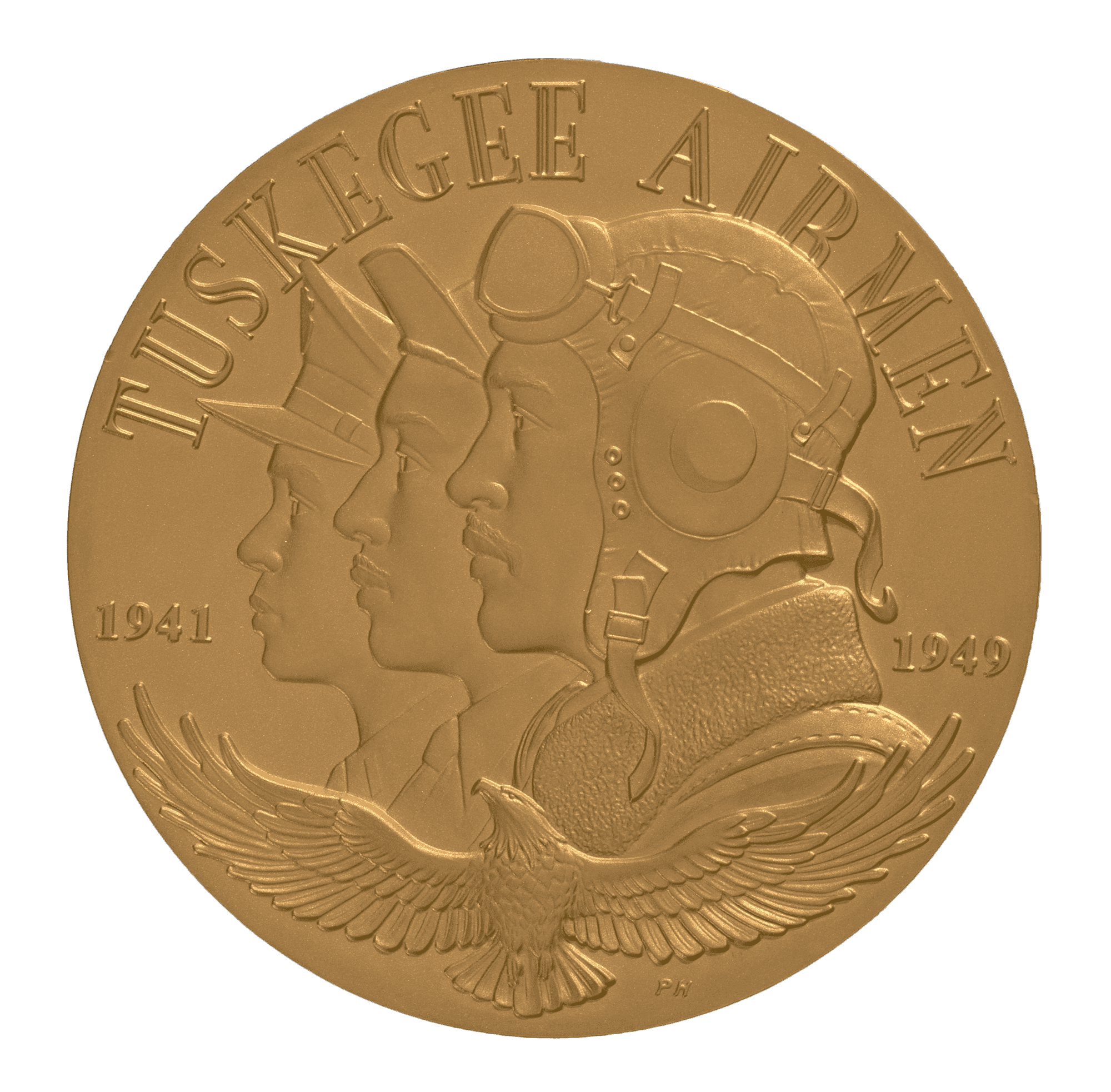

Training the Tuskegee Airmen

Tuskegee Airman servicing a P-51 Mustang airplane

Recruits training in basic and advanced flying

Thirteen African American men volunteered for the first flight training program at Tuskegee Institute. Many more followed, determined to serve their country and prove that African Americans could be top fighter pilots. Between 1942 and 1946, 992 pilots graduated from Tuskegee Army airfield and earned their pilot’s wings.

Graduates eventually joined the 332nd Fighter Group under Col. Benjamin O. Davis Jr. They gained special recognition for their record of safely escorting bombers on their missions. The Tuskegee Airmen helped put to rest doubts about the abilities of African American pilots.

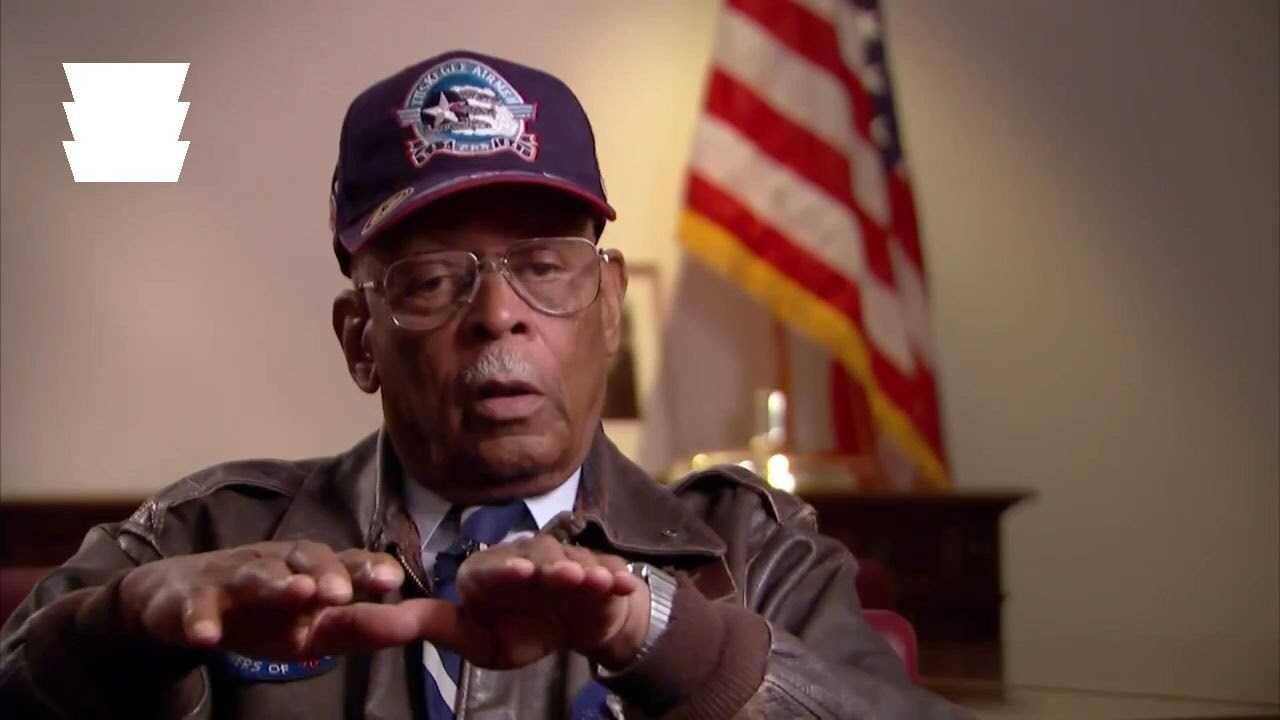

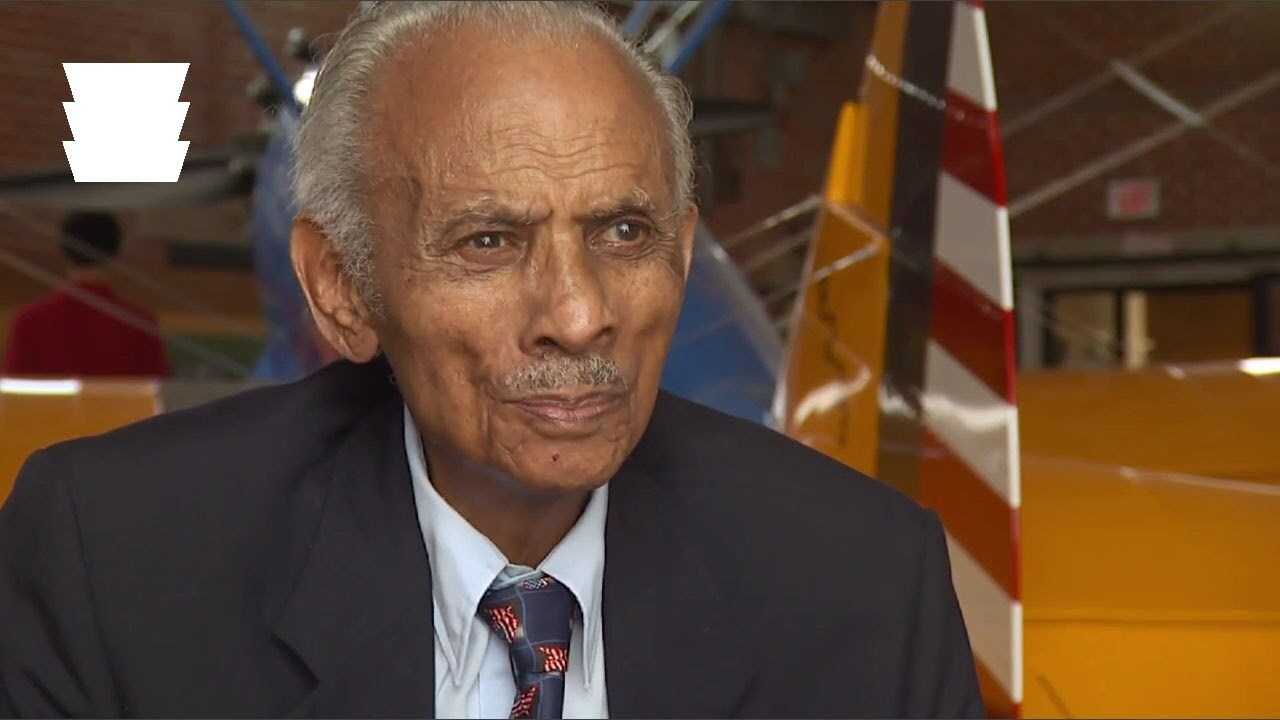

Featured Video

The Tuskegee Airmen

Tuskegee Airmen tell their stories in their own words.

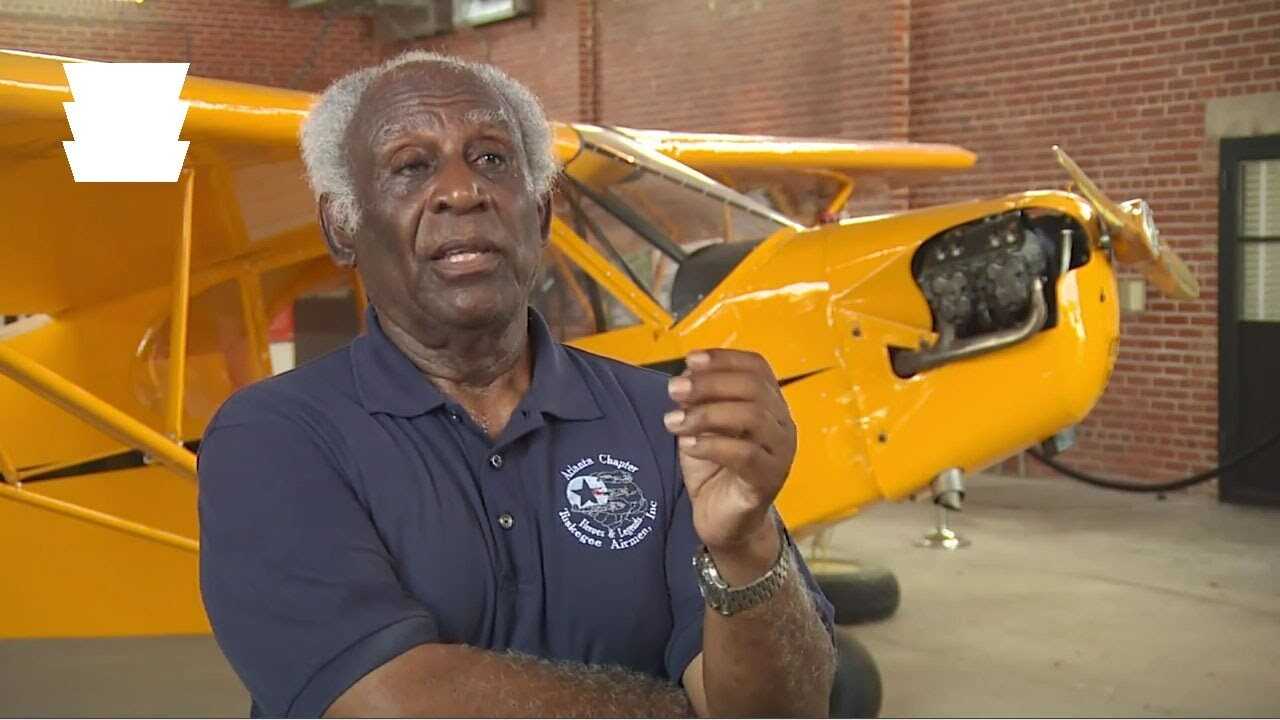

Featured Constellation

Tuskegee Airmen Kaydet

African American fighter pilots learned to fly using this plane at Moten Airfield in Tuskegee, Alabama. Today, the Tuskegee Airmen are celebrated for their contributions and sacrifices during World War II.

Tuskegee Airmen Share Experiences

Airmen recount some of their training and combat experiences during World War II.

Pushing for Permanent Change

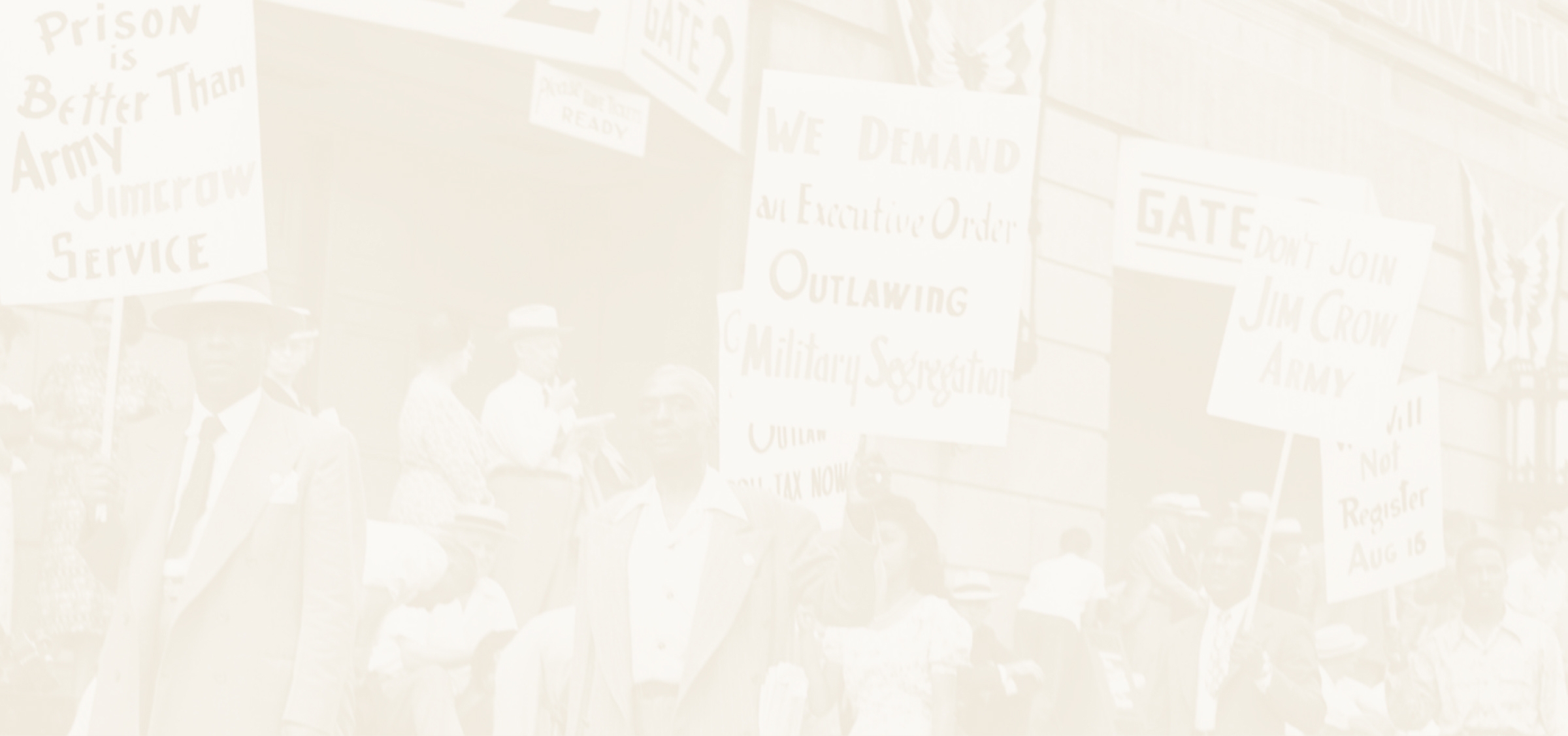

A. Philip Randolph leads protest against segregated military

After World War II, union leader A. Philip Randolph, the NAACP, the Urban League, and other civil rights groups renewed their demands for ending discrimination in the military. They pressed the federal government to make the Fair Employment Practices Commission permanent, but Congress cut off its funding in 1946.

President Harry Truman convened the President’s Committee on Civil Rights that same year. The committee recommended an immediate end to discrimination in the armed forces. It also demanded anti-lynching legislation and better protection for voting rights. To get around a resistant Senate, Truman forced the armed forces to integrate by issuing Executive Order 9981 in July 1948.