Historic Event

Atlanta Washerwomen Strike

Washerwomen

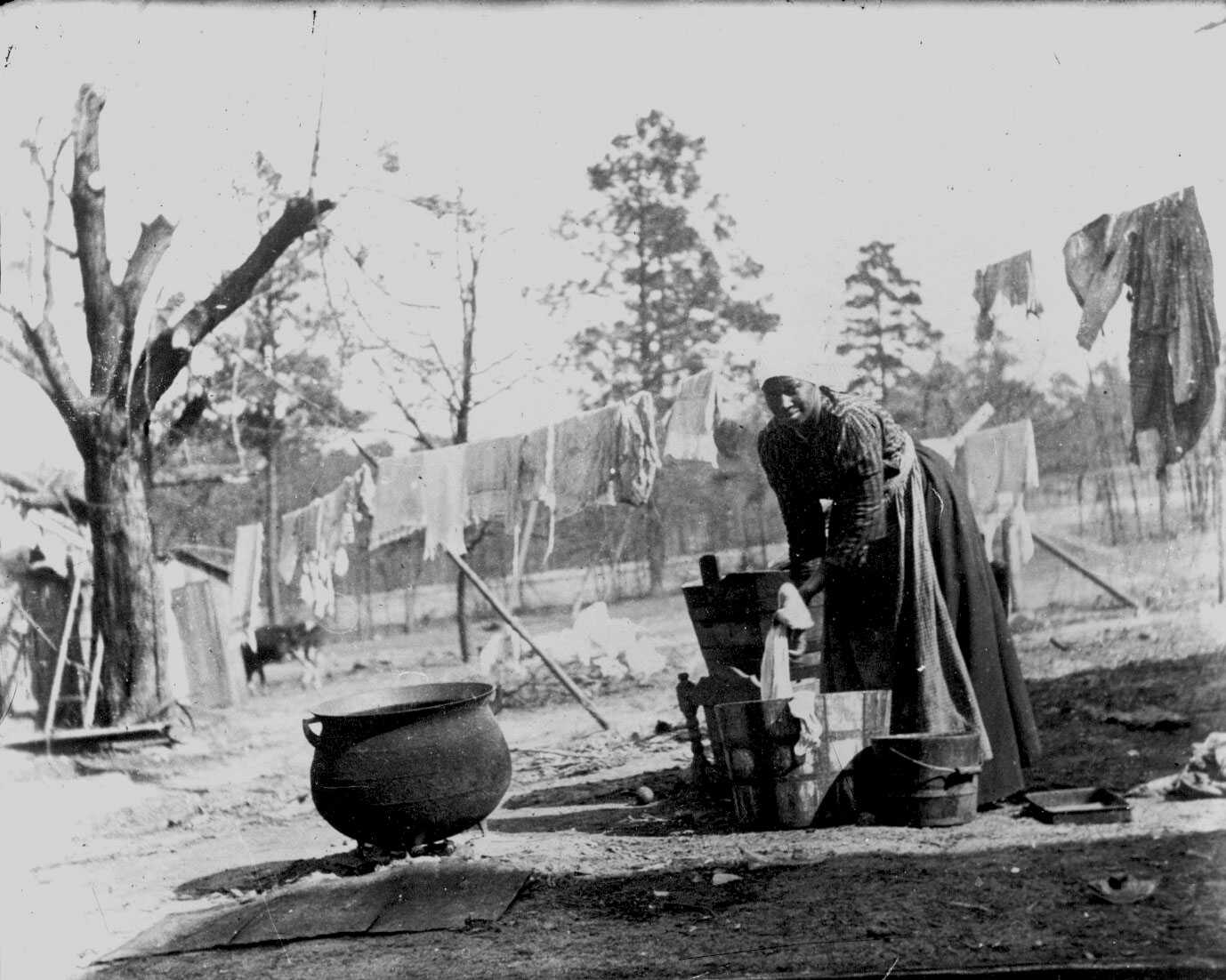

Washerwoman in Suwanee, Florida, ca. 1902

In the last quarter of the 19th century, most African American women worked as washerwoman or domestic servants. Many white families, poor and well-to-do alike, relied on washerwomen to wash their clothing and household linen. However, efforts by African American women to increase their wages were consistently met with resistance. In 1881, washerwomen in Atlanta staged the largest-ever strike by African Americans, walking off the job for weeks until their demands and those of other service workers were met.

Unfair Conditions

Women doing washing, Jefferson County, Florida

Working conditions for washerwomen were difficult and demanding. They made their own soap from a combination of lye, starch, and wheat bran and used washtubs made from beer barrels to wash clothes. They carried gallons of water from wells, pumps, or hydrants in order to wash, boil, and rinse clothes. After being washed, clothes were wrung by hand and hung out to dry. Finally, clothing was ironed using heavy metal irons and carefully folded before being returned to the customer.

The work week typically began on Monday and lasted until the last clean clothes were delivered on Saturday. Women employed as laundresses also had to care for their own families. In Atlanta, washerwomen typically earned between $4 and $8 per month but were subject to customer whims—they were frequently underpaid or not paid at all.

"We Mean Business... or No Washing"

Washboard

Wash pot used by Manda Caldwell and her daughter Susan Caldwell McGill

Frustrated by low wages and unfair treatment, 20 women went on strike in Atlanta in the summer of 1881. They formed a union—The Washing Society—and demanded a consistent rate of $1 per dozen pounds of clothes. The strike was also strategically timed to coincide with Atlanta’s hosting of the International Cotton Exposition. Knowing the city could not afford a major economic disruption, Washing Society members went door to door generating support from both Black and white washerwomen. With the help of Black ministers, they held a large meeting and gave speeches calling for others to join them. Within three weeks, the Washing Society grew from 20 to 3,000 strikers.

Article from The Washington Star about the Atlanta washerwomen’s strike, August 9, 1881

Winning Better Wages

Woman washing laundry near Augusta, Georgia

In response to the strike, local authorities began fining, threatening, and arresting Washing Society members and strikers. In an effort to stop the strike, city officials proposed that members of the organization pay a $25 annual fee, an enormous sum at the time. The city also offered tax incentives to entrepreneurs who wanted to create steam laundries to replace the laundresses. The washerwomen surprised city officials by agreeing to pay the $25 fee in return for a consistent fee scale.

Inspired by the washerwomen, other domestic workers including hotel workers made their own demands for higher wages. The growing unrest increased concerns in the business community so much that the Atlanta City Council dropped the proposed licensing fee. With this concession, the laundresses had finally improved their economic condition.

We the members of our society, are determined to stand to our pledge and make extra charges for washing... and are willing to pay $25 or $50 for licenses as a protection, so we can control the washing for the city.

Atlanta Washing Society Members, 1881