Chapter 4

Pushing for Permanent Change

African Americans, along with their allies, pushed to secure civil rights by changing America’s laws. Through large demonstrations and marches, activists brought the nation’s attention to the struggle for civil rights and full citizenship.

But some younger African Americans wanted more direct results. Frustrated by the slow, gradual change of the Civil Rights Movement, they looked to the Black Power Movement and its demands for immediate equality.

Defining Black Power

The term “Black Power” had its roots in the nationalism of Marcus Garvey and the militancy of Malcolm X. Stokely Carmichael, the chairman of SNCC, first used the phrase in 1966 at a Mississippi rally.

The term contains many ideas: rejection of integration, African American community control, skepticism of nonviolence as a strategy for social change, and the promotion of Black pride. Black nationalists and Black militant organizations used Black Power as a rallying cry, and its ideas fueled a renewed interest in Black history and African heritage.

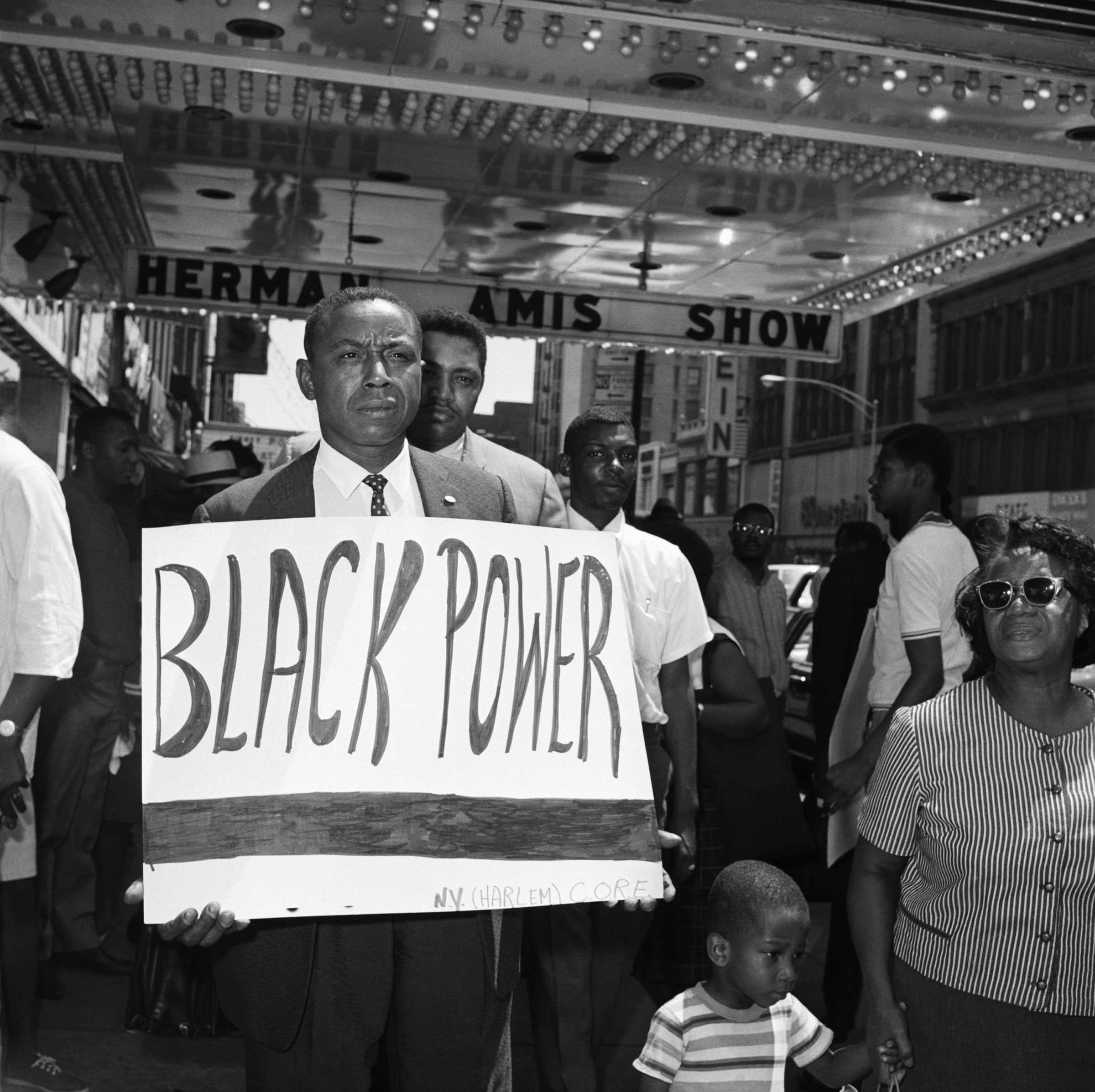

The national director of the Congress of Racial Equality, Floyd B. McKissick, supported the idea of Black Power.

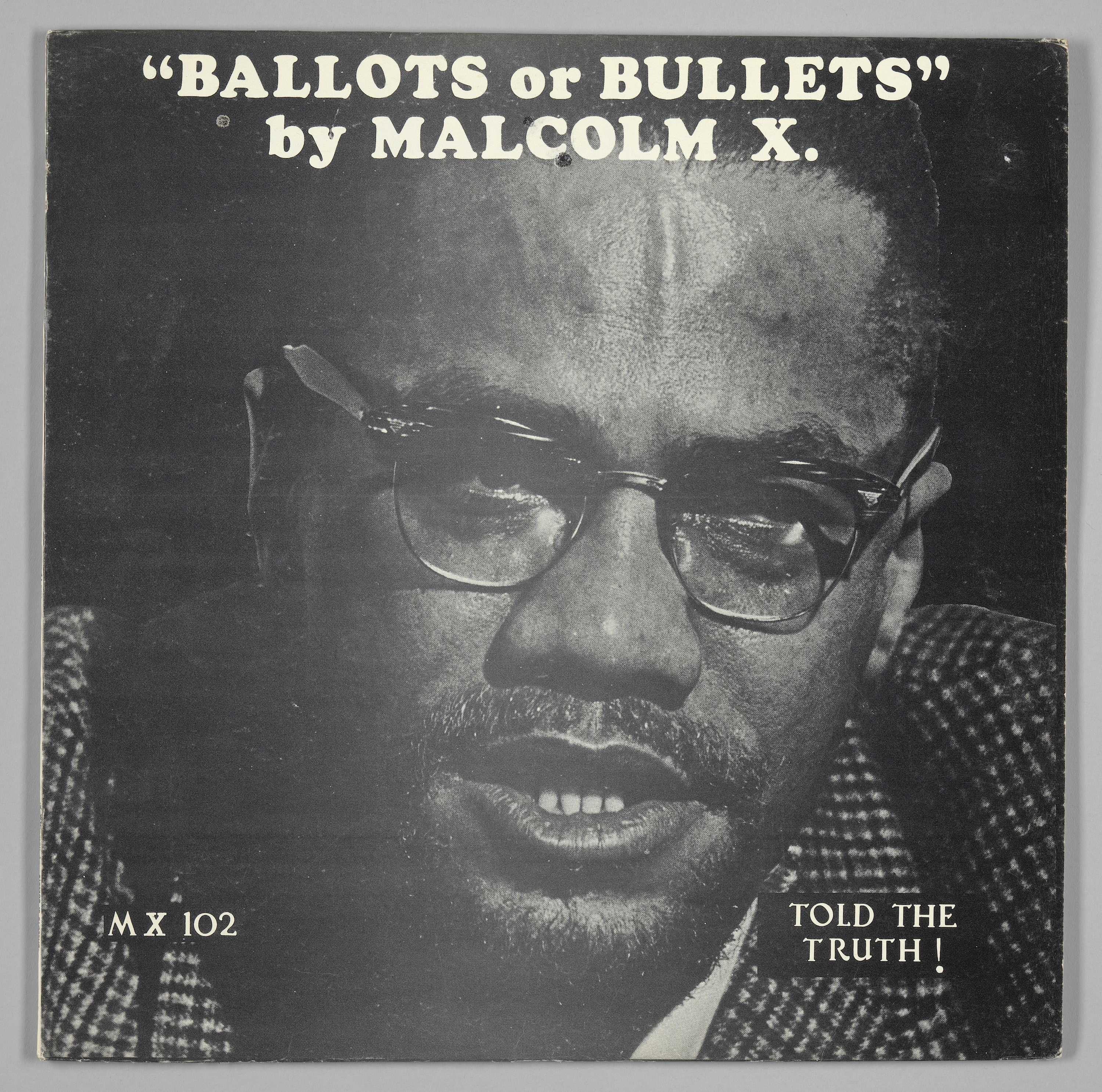

We declare our right on this earth . . . to be a human being, to be respected as a human being, to be given the rights of a human being in this society, on this earth, in this day, which we intend to bring into existence by any means necessary.

Malcolm X, 1964

Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam

Malcolm X speaking at a rally in Harlem

Malcolm X was an influential figure in the Nation of Islam (NOI) in the 1950s and early 1960s. His brilliance as a speaker and his militant advocacy helped generate a tenfold increase in NOI membership.

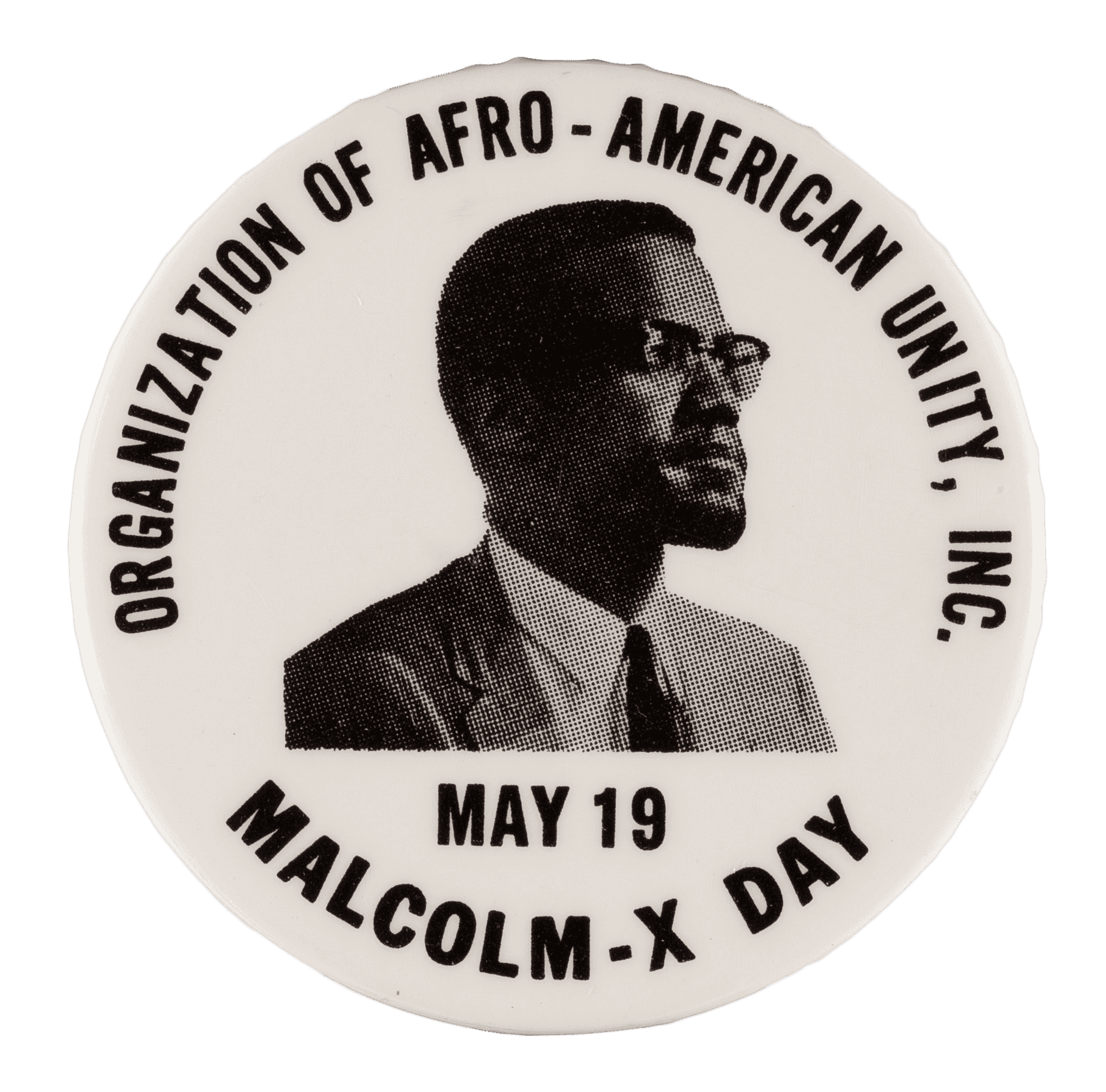

By the mid-1960s, Malcom X split with the Nation of Islam, viewing the African American struggle for human rights as part of a larger international struggle. After traveling abroad, he returned to America and founded the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU) in 1964. Malcolm X was assassinated on February 21, 1965, by three NOI members.

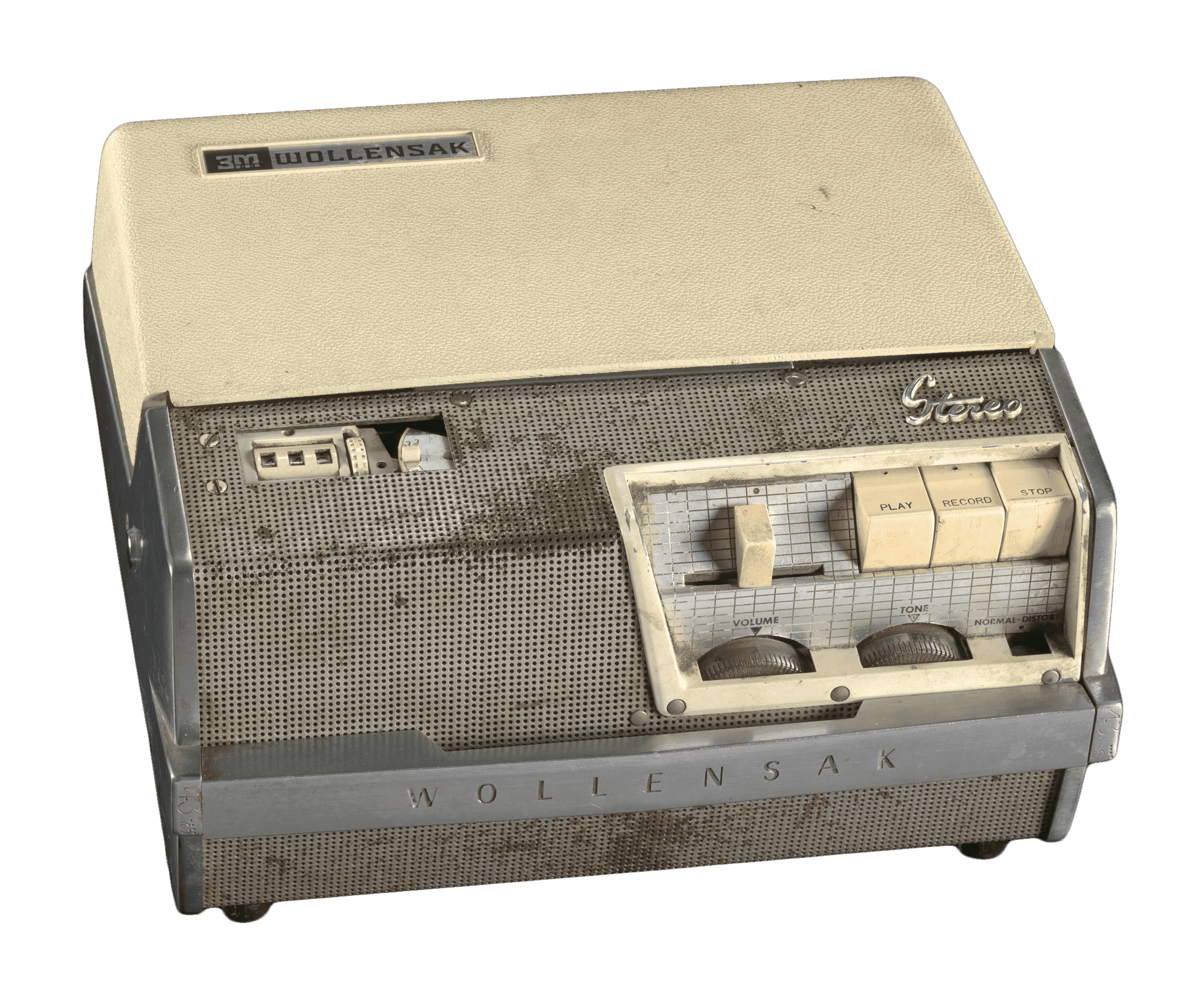

Malcolm X’s Tape Recorder

Malcolm X was an activist and Muslim minister known for his speeches promoting Black self-determination and self-defense. As a minister at the Nation of Islam Temple #7 many of his speeches and lectures were recorded.

The Organization of Afro-American Unity

Organization of Afro-American Unity leaflet

After his trip to Mecca in 1964, Malcolm X created the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU), which reflected his new international views. The OAAU’s goal was to connect African Americans to their African heritage, encourage economic cooperation between people of African descent, and fight for African American human rights.

Robert Williams’s Political Shift

Robert Williams in England

Robert F. Williams was president of the Monroe, North Carolina, NAACP, an organization long dedicated to nonviolence. But by 1959, Williams began to tell African Americans to meet “violence with violence,” earning him a suspension from the national NAACP. Upon learning he was the subject of an FBI investigation, Williams fled to Cuba. There he wrote a book, Negroes with Guns, and hosted a radio show. His views influenced later groups like Deacons for Defense and Justice, SNCC, and the Black Panther Party.

Deacons for Defense and Justice

Formed in 1964 in Jonesboro, Louisiana, the Deacons for Defense and Justice included Korean War and World War II veterans. Having seen harassment and violence directed at civil rights activists, the Deacons organized to protect Black communities. For instance, when Klan members drove through Bogalusa, Louisiana, firing weapons, the Deacons fired back. The original Jonesboro chapter grew to include 21 others in Louisiana, Alabama, and Mississippi. At civil rights protests and voter registration drives, the Deacons became a silent but visible presence.

In civil rights marches and protests, women wore hatpins like this and used them for self-defense.

Stokely Carmichael

Stokely Carmichael (right) and Angela Davis

Stokely Carmichael gives the Black Power salute at a rally in New York.

Born in Trinidad and Tobago and educated at Howard University, Stokely Carmichael (later Kwame Ture) joined the Civil Rights Movement as a teenager, spending 42 days in a Mississippi prison during the Freedom Rides. Afterwards he joined SNCC and helped register voters in Alabama, becoming SNCC’s chairman in 1966. But Carmichael left SNCC a year later to join the Black Panther Party, where he argued for a confrontational, even violent approach to African American liberation.

The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense

The Black Panther Party was founded in Oakland, California, in 1966 by Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale. They preached a militant liberationism—armed self-defense and an immediate end to Black oppression. The Black Panther Party represented the growing outrage among African Americans over the country’s slow pace of change. The Black Panthers quickly came into conflict with police and the FBI, and after a series of arrests and trials, their influence waned.