Community Story

Black Power and 'The Black G.I.'

Documenting Black Experience on the Ground

In 1970, filmmaker Kent Garrett was granted permission by the Pentagon to bring a documentary crew to Japan and Vietnam to produce an episode of the WNET public affairs program Black Journal. While Pentagon officials hoped Black Journal would paint a positive portrait of the African American military experience, Garrett produced a nuanced, even subversive film. The Black G.I. functions as a primary source of Black military life during Vietnam, where Black servicemen from different branches of the military speak candidly about their experiences of war, their identities as Black people, and their encounters with prejudice at home and abroad.

Featured Video

Black Power, Black Pride, and Black Togetherness

Black Journal emerged during a time with an increased push for African American representation in publicly funded television programs. It was also a time of heightened social tensions, particularly concerning race and the Vietnam War. Both at home and abroad, ordinary individuals became more assertive in declaring their views. The intersection of race and war are clear in the narrator’s question about “whether the real war is in Vietnam or America.”

Different Experiences Across the Armed Forces

Though shepherded through Vietnam and Japan by Pentagon-sponsored Public Information Officers, Garrett and his crew were still able to conduct candid interviews with African American servicemen. This achievement speaks to the trust the filmmakers engendered, as well as to the courage of the military men, many of whom could have faced retaliation or disciplinary actions for their comments. Both officers and enlisted men were willing to speak about the obstacles they faced.

“Strictly a Black Thing”

Black servicemen maintained their racial pride against the backdrop of encounters with prejudice. Some describe as hypocritical the reality of fighting for a country where de facto segregation still exists. Soul music, natural hair, and dashikis became proxy battles for broader cultural and political issues.

Featured Video

Footage of Koza Four Corners, a section of an Okinawan city where shops and entertainment for Black servicemen developed.

Tensions between Black and white servicemembers, and between servicemembers and local Okinawans, boiled over more than once, including during the Koza Riots.

"We Know Black Culture, We Are the Black People"

For the servicemen interviewed in The Black G.I., three topics are repeatedly mentioned – dashikis, Afros, and Soul music. All three of these elements played a major role in Black cultural formation in the 1960s and 1970s. Dashikis, a West African pull-over style tunic, became a popular cultural signifier in the late 1960s. Afros, a natural hairstyle, were also an assertion of cultural and racial independence, while the Soul music of the time featured artists who spoke directly – and critically – about the political, social, and cultural controversies of the day.

I think that when you begin to talk with so many of these young men about soul music, they’re really talking about a lot of other things. “Soul” is just a convenient handle that they think we immediately recognize as being a legitimate complaint, but behind it are a whole malaise of not very good conditions.

L. Howard Bennet, Pentagon Deputy Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights

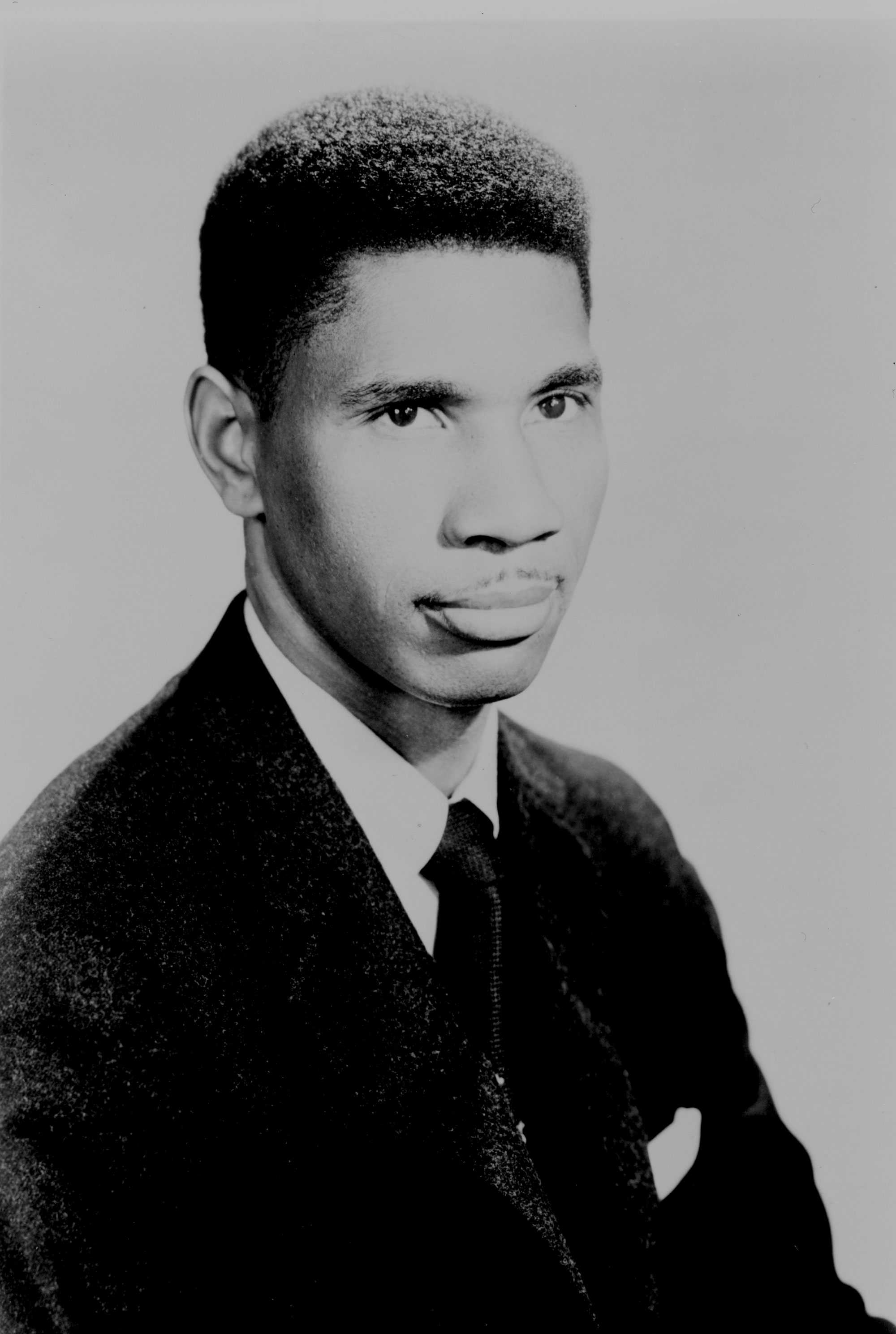

Sylvester Bracey’s Viral Video

In 2020, Sylvester Bracey III, then 22 years old, saw a viral clip from The Black G.I. on Twitter and immediately recognized his grandfather, as recounted in this NBC News article. Bracey III had grown up hearing stories about the documentary and about his grandfather’s experiences in Vietnam – including his experiences with racism. Bracey III related how his grandfather’s commitment to Black Power and equal rights, nurtured while in Vietnam, carried through for the rest of his life. Sylvester Bracey suffered from liver and kidney ailments due to Agent Orange exposure and died from heart disease just months before the video went viral, never having seen himself in The Black G.I. His legacy, and that of all the men who spoke bravely of their experiences, lives on through this film.

It makes me wonder if a lesson my father instilled in me, was birth[ed] from his Vietnam experience. My father used to say “Don’t let your position of authority, make you lose your sense of humanity.”

Sylvester Bracey Jr.

Afterlife of the Black G.I.

The Black G.I. features interviews with many unnamed servicemembers. This was most likely done for their protection. Black servicemen utilized their anonymity to speak freely about their experiences and opinions, but because The Black G.I. aired while many of the men were still overseas, few of the participants actually saw it.