Chapter 5

Challenging Poverty and Discrimination

In 1964 President Lyndon B. Johnson announced his Great Society initiative, which included efforts to reduce poverty. He hoped to accomplish these goals by developing job skills, providing educational opportunities, and increasing housing options. While some programs were successful, poverty continued to plague portions of the country.

During the 1960s, African Americans had a poverty rate three times higher than white Americans. This was particularly true in urban areas where unemployment, underemployment, and inadequate educational opportunities made earning a living difficult.

The Struggle Continues

For all their influence, the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act did not address all forms of racial injustice. These federal laws did not end violence against civil rights workers, state laws against interracial marriage, or other forms of racial discrimination, including housing discrimination. After 1965, activists turned their efforts to changing housing laws, fighting poverty, and improving employment opportunities for African Americans.

James Meredith’s March Against Fear

James Meredith holding newspaper announcing his enrollment

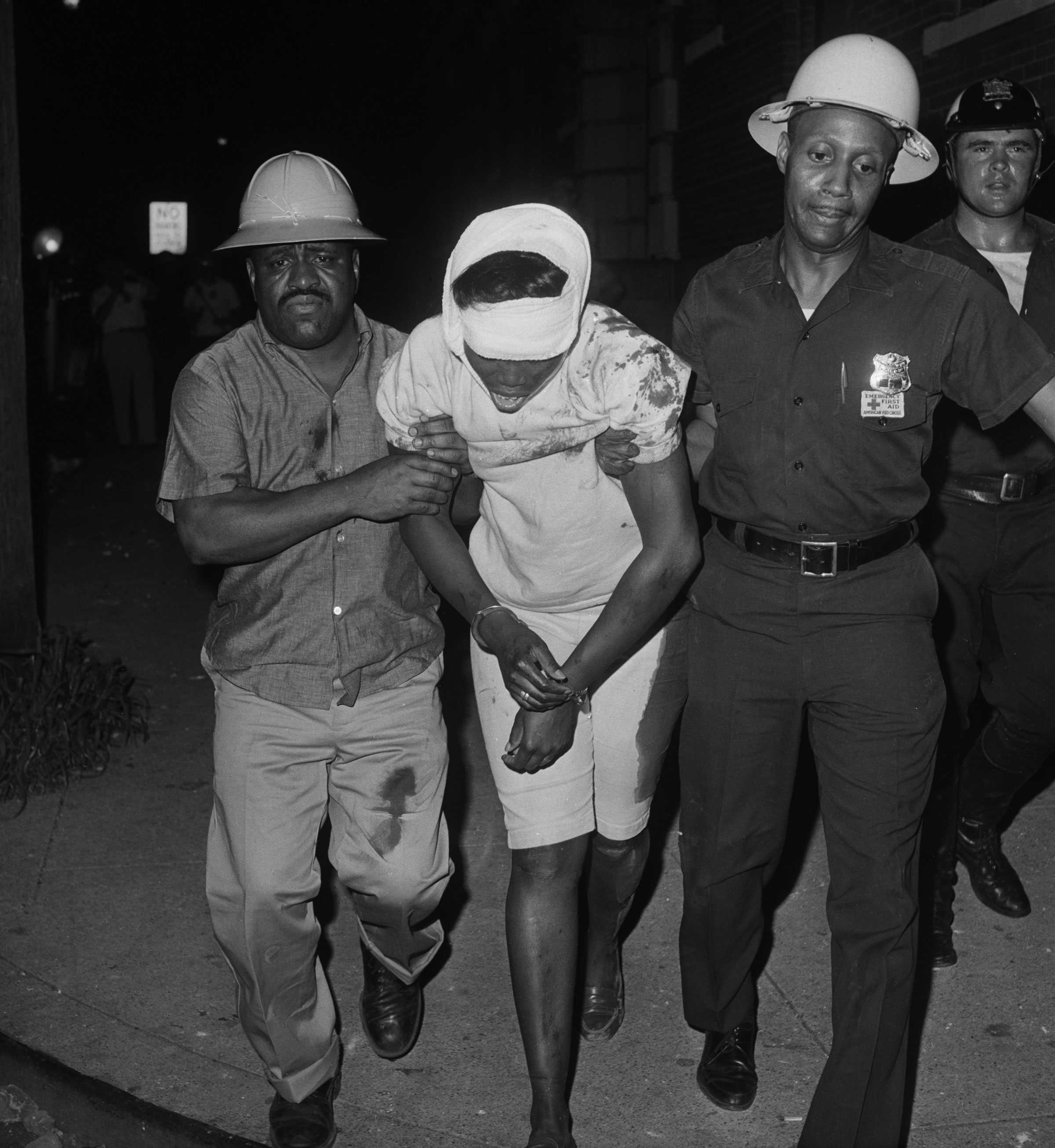

Sensitive Content

The image includes graphic and violent imagery.

James Meredith after he was shot during his March Against Fear

In 1961, James Meredith integrated the University of Mississippi as an undergraduate student. Several years later, in 1966, Meredith launched a March Against Fear to protest violence against African Americans in Mississippi. His plan was to march from Memphis, Tennessee, to Jackson, Mississippi, but when he crossed the border into Mississippi he was shot. Other protesters, led by Martin Luther King Jr. and Stokely Carmichael, continued the march while Meredith recovered.

Featured Video

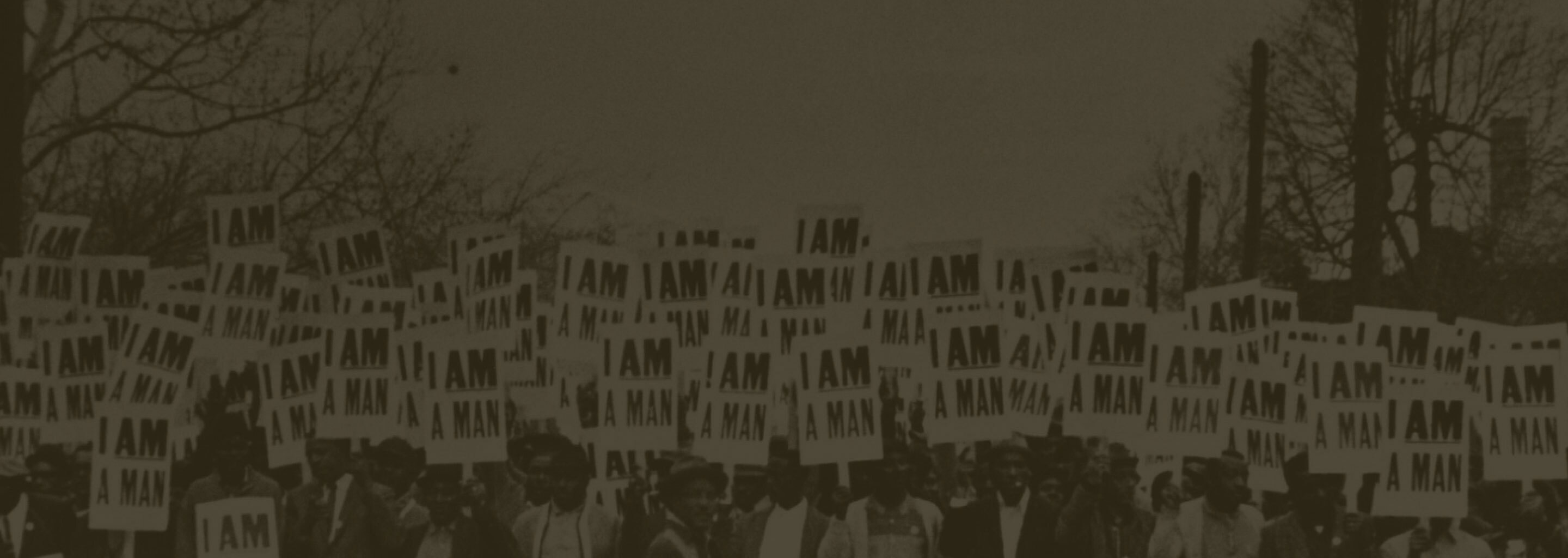

Urban Rebellions

This video chronicles a series of uprisings by Black urban residents that took place in Cleveland, New York, Newark, Los Angeles, and other cities across the country between 1964 and 1968. The rebellions grew from frustrations with police violence, economic difficulties, and other causes. Martin Luther King Jr. described this civil unrest as the “the language of the unheard.”

A riot is the language of the unheard. And what is it America has failed to hear? It has failed to hear that the plight of the Negro poor has worsened over the last few years. It has failed to hear that the promises of freedom and justice have not been met. And it has failed to hear that large segments of white society are more concerned about tranquility and the status quo than about justice, equality, and humanity.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., 1968

Loving v. Virginia

Interracial Marriage

Mildred and Richard Loving

Mildred Jeter, an African American woman, and Richard Loving, a white man, were married in the District of Columbia but preferred to live in Virginia. But interracial marriage was illegal in Virginia, and they were arrested, convicted, and told to leave the state. Mildred wrote to Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy asking for assistance, and he directed the Lovings to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).

With the help of the ACLU, the Lovings appealed their case to the U.S. Supreme Court. In Loving v. Virginia, the Court held that Virginia’s law barring interracial marriage violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. The unanimous decision deemed all state laws banning interracial marriage to be unconstitutional.

The Evolution of Martin Luther King Jr.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. at Chicago Freedom Movement rally, 1966

In 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. traveled to Memphis, Tennessee, to support the demands of striking sanitation workers.

By the late 1950s, Martin Luther King Jr. had become the leading spokesman of the Civil Rights Movement. He led protests throughout the 1960s, won the Nobel Peace Prize, and gave one of the most famous speeches in American history, “I Have a Dream,” at the March on Washington in 1963.

After 1965, King examined issues of injustice beyond the South and explored the connection between poverty and discrimination, especially in urban areas. By 1968 he was planning the Poor People’s Campaign, which would bring thousands of demonstrators to Washington to demand economic justice.

The Struggle Continues

After the 1965 Voting Rights Act passed, civil rights activists believed there was still more to accomplish and focused their attention on passing the Fair Housing Act. The act outlawed housing discrimination and was passed by the Senate after extensive debate and the ending of a southern-led filibuster. In the aftermath of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, and with pressure from President Lyndon B. Johnson, the House of Representatives approved the Fair Housing Act on April 10, 1968. The original 1968 act prohibited discrimination in the sale, rental, and financing of housing based on race, religion, and national origin. The law was later expanded to include sex discrimination, discrimination against people with disabilities, and discrimination against families with children.