Forming Networks

The Histories of Roosje, Jan Smeising, and William P. Powell Sr.

Enslaved people were forced to make lives for themselves under racial slavery. In the face of constant instability, violence, and uncertainty, enslaved people built communities and established networks of support.

The stories of Roosje, Jan Smiesing, and William P. Powell Sr. provide windows into some of these diverse networks—from kinship networks in the colony of Berbice, to medicinal healing networks in southern Africa, to maritime abolitionist networks connecting the United States and the United Kingdom.

Kinship Networks

Field cradle

Slavery and colonialism fractured the emotional and cultural ties of captured Africans. In the face of familial separation, enslaved people built new communities and formed kinship networks that expanded beyond blood relatives.

In enslaved communities, collective child-rearing was common. These networks of support guaranteed that childcare could continue even through parental death or sale. These kinship networks softened the emotional pain of life under slavery and were essential to the survival of individuals and communities.

Slavery and Motherhood

Enslaved mother and child, Salvador de Bahia, Brazil, 1884

Lucinda and Frances Hughes with their children in Virginia, United States, ca. 1861

Motherhood was a complex experience for enslaved women. The common practice of separating mothers from their children caused unimaginable grief. However, the experience of motherhood often reflected an important rite of passage.

While enslavers regarded children as valuable laborers essential to the plantation’s success, for the enslaved, the presence of children represented hope and the continuation of life and cultural identities. Under challenging circumstances, enslaved women maintained and transformed African-derived mothering practices to sustain their communities.

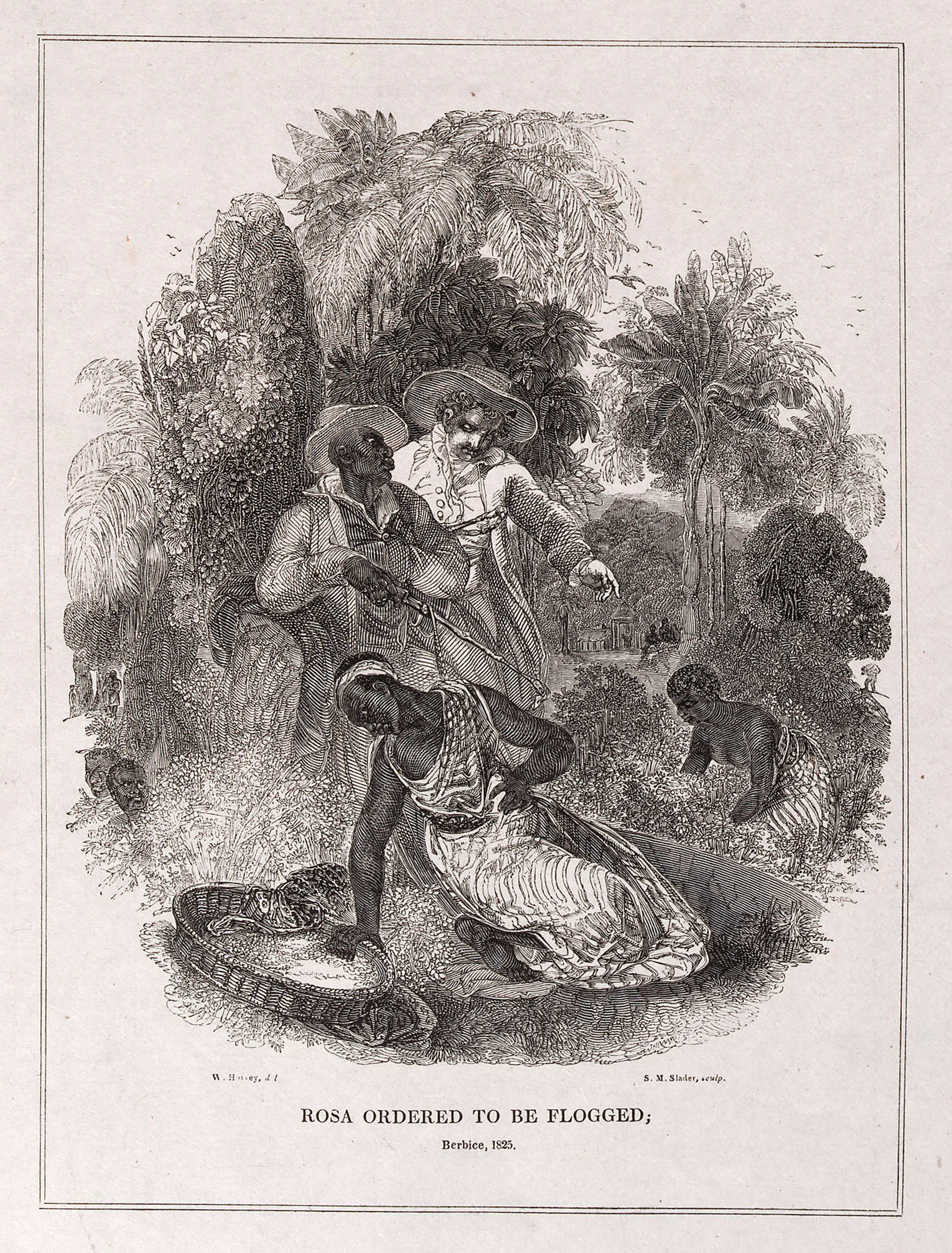

Roosje

Roosje was an enslaved field worker on a coffee plantation in the Dutch, later British, colony of Berbice. In 1819, while visibly pregnant, Roosje was flogged, or whipped, at the orders of the plantation manager. The following evening, in the presence of her husband, sisters, and an enslaved midwife, Roosje delivered a bruised, stillborn baby.

Roosje pursued legal justice for herself and her child in the colonial court. She filed a formal complaint against the plantation manager, citing the punishment she received as the cause of her miscarriage. Her mistreatment and the legal case that followed became a rallying cry for abolitionists across the Atlantic.

Roosje’s trial points to the importance of kinship networks in the lives of enslaved people. Roosje’s voice is amplified by the testimonies of her loved ones, including her husband George, her sisters Claartje and Ariaantje, and her midwife Marianna.

Enslaved people gather on a plantation in Cuba, ca. 1860

Healing Networks

Healer in 19th-century Brazil

Healers were essential to the survival of enslaved communities. The deadly realities of slave labor and substandard living conditions made enslaved people extremely vulnerable to a wide variety of illnesses. Enslavers provided limited, if any, treatment for these ailments.

Herbalists, spiritual healers, bonesetters, and midwives met community needs on their own terms. These practitioners used traditional African knowledges, exchanged information with Indigenous peoples, and formed networks to pass their expertise to new generations. Treating fellow enslaved people was a revolutionary act that helped restore bodily autonomy stripped away by enslavement.

Jan Smiesing

Notes from a Healer

Jan Smiesing’s Journal

Remedy from Jan Smiesing’s Journal

The Slave Lodge was founded in 1679 to house enslaved people owned by the Dutch East India Company on the Cape Colony in southern Africa. Jan Smiesing, the son of an enslaved Malay woman and a Dutch official, lived and worked there as a schoolmaster and healer.

In his personal journal, Smiesing recorded remedies he used to treat “company slaves.” His treatments reveal the wide range of ailments afflicting the enslaved—from fevers to diseases related to sexual abuse. As a healer, Jan Smiesing filled a void in medical care for the enslaved population at the lodge, bringing humanity into an inhumane space.

Medicinal Plants

From healing salves to teas, herbal medicines aided enslaved people and communities around the Atlantic world. These four plants are among the many used by enslaved people.

Maritime Networks

Illustration of abolitionist Mahommah Gardo Baquaqua. Pola Maneli, 2024

The slave trade turned the sea into a site of violence and horror. However, Black people navigated those same waters, creating spaces of freedom and routes of resistance.

Black seafarers found mobility unexperienced elsewhere, earning money and traveling the world. Black abolitionists created clandestine networks, passing on politics, information, and aid to other freedom seekers. Enslaved people used these networks to escape, seeking passage and refuge in ports around the world.

William P. Powell Sr.

William P. Powell Sr. was a prominent African American abolitionist who spent his early career as a seaman. Inspired by his time at sea, Powell established a trade union and boarding home for Black sailors to aid the “moral and social elevation of the black Sons of the Ocean.”

In 1851, the Powell family moved to Liverpool, England, to escape discrimination in the United States. William and his wife, Mercy, continued their work against slavery, expanding their abolitionist networks internationally by hosting American abolitionists and supporting enslaved escapees who came to Liverpool by sea. Over his lifetime, Powell assisted as many as 1,500 people to freedom.

I will take to water. This very bay shall yet bear me into freedom.

Frederick Douglass, abolitionist, 1849