Chapter 3

Protesting and Marching for Civil Rights

African Americans resisted segregation through individual and collective action. Privately, they attended to their families, their communities, and their lives. Publicly, they boycotted, marched, and protested, forcing businesses and cities to desegregate.

Organizations such as the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) provided training and funding for desegregation efforts.

Rosa Parks Sparks a Boycott in Montgomery

Dress sewn by Rosa Parks

Rosa Parks’s mug shot

In 1955, when Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat, she set off a chain reaction that fueled the Civil Rights Movement. Her arrest in Montgomery, Alabama, sparked a local bus boycott that lasted 381 days, and press coverage made the boycott national news.

Rosa Parks was a civil rights activist long before her arrest—she had been a 12-year NAACP member and secretary of its Montgomery, Alabama, chapter.

Rosa Parks was not the first Black woman arrested for defying segregated bus seating. Claudette Colvin was arrested in March 1955, but she was only 15 years old, and the NAACP lawyers did not think hers would be the best test case.

Whatever my individual desires were to be free, I was not alone. There were many others who felt the same way.

Rosa Parks

The Montgomery Bus Boycott

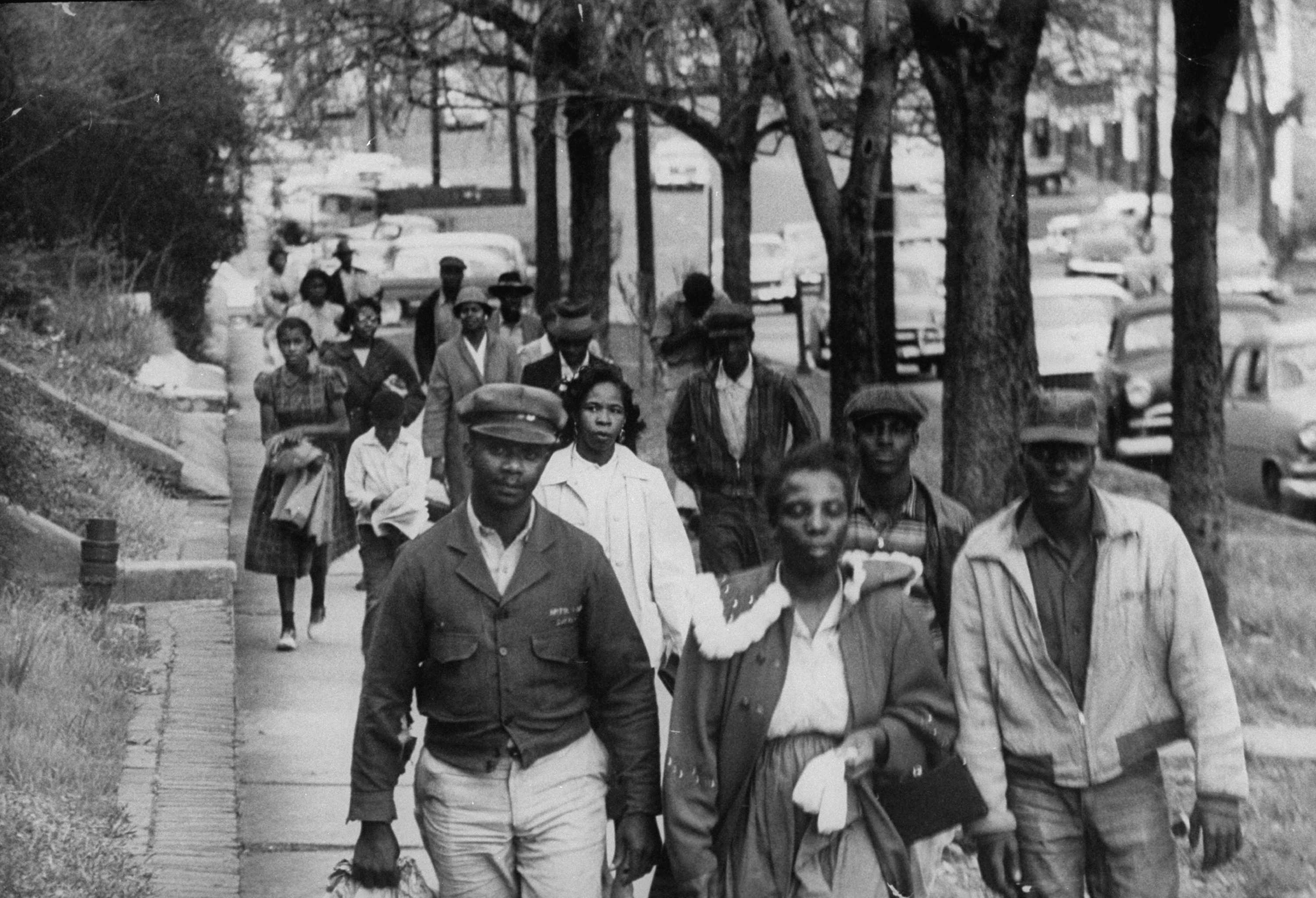

Montgomery residents carpool during the boycott

Rosa Parks’s arrest and conviction set in motion a campaign to boycott buses in Montgomery, Alabama. The idea of a one-day bus boycott was circulated in a flyer created by the Women’s Political Council. The idea gained momentum, and soon, nearly 40,000 African Americans refused to take the bus.

That evening a new organization headed by Martin Luther King Jr.—the Montgomery Improvement Association—was formed to lead the protest. African Americans refused to ride buses for more than a year, and King and other activists were arrested. In 1956 the Supreme Court ruled that bus segregation was unconstitutional, and the boycott and segregated seating came to an end.

Featured Video

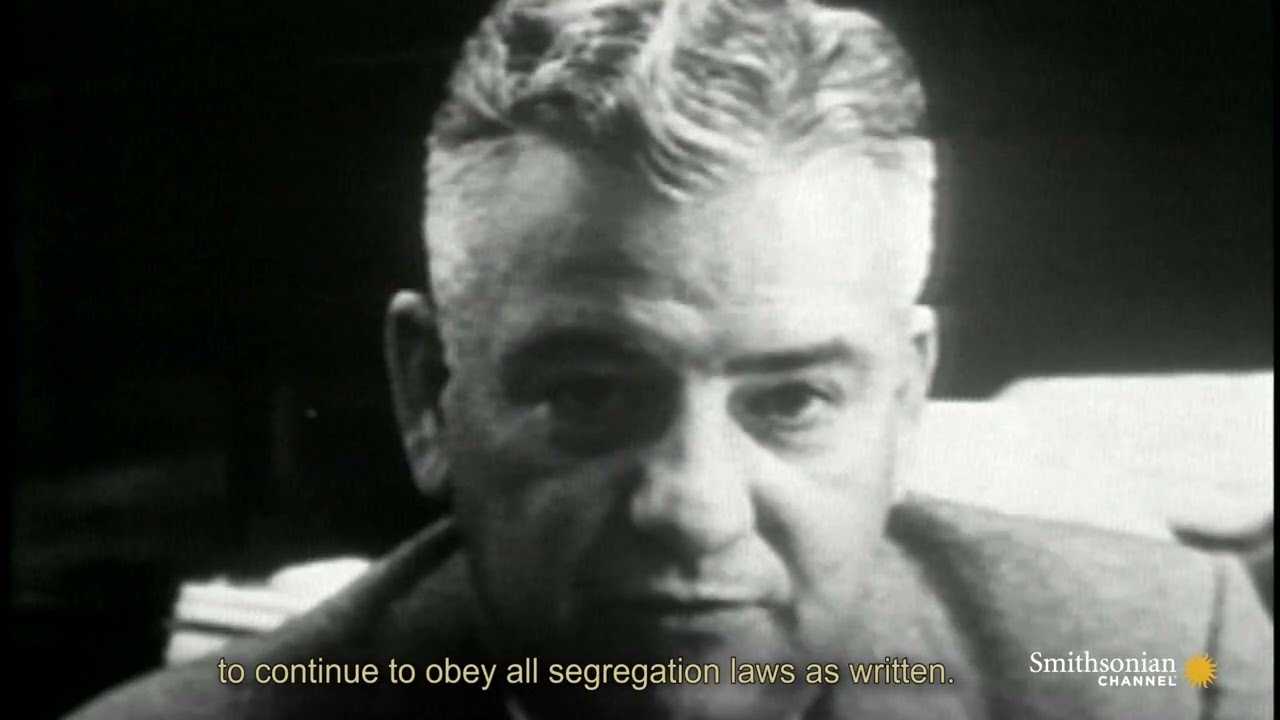

Montgomery Bus Boycott News Coverage

The bus boycott in Montgomery received extensive news coverage in print, radio, and television across the nation and around the world. This video shows how the growing influence of television news shone a light on the injustices of segregation.

Jo Ann Robinson and the Women’s Political Council

Jo Ann Robinson’s mug shot

As president of Montgomery’s Women’s Political Council, Jo Ann Robinson led the group’s fight against segregated bus seating. When Rosa Parks was arrested, Robinson printed and distributed a flyer calling for a one-day bus boycott, which quickly grew into an open-ended protest. Throughout the boycott, Robinson endured threats and police harassment.

Fred Gray, Attorney

Fred David Gray

Fred Gray was Rosa Parks’s attorney. A longtime opponent of segregation, Gray filed a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of Alabama’s state law and Montgomery’s city ordinance mandating bus segregation. The case eventually reached the U.S. Supreme Court, which affirmed in Browder v. Gayle that segregation laws were unconstitutional, ending segregated busing.

Gray continued his civil rights litigation, challenging school segregation, defending the NAACP against a proposed ban in Alabama, and representing Martin Luther King Jr. in a tax evasion prosecution. He later represented the survivors and families of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, in which government doctors denied medical treatment to African American men suffering from disease.

Civil rights activists ride a desegregated bus in Montgomery

Earlier Public Transportation Boycotts

Union Transportation streetcar in Nashville, Tennessee

Boycotting public transportation did not begin in Montgomery, Alabama. African Americans had refused to ride streetcars in 25 southern cities between 1900 and 1907 in protest of segregation laws. African Americans hoped the loss of their business would lead companies to support their cause, especially in cities with many Black riders.

Bus Boycott in Baton Rouge

In 1950, officials in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, outlawed the city’s only independent Black-owned bus company. After the ruling, African Americans were forced to ride segregated buses and sit in designated sections at the back of the bus, even though they were 80 percent of Baton Rouge’s bus riders. After Black riders organized a boycott in 1953, the city compromised, making seats available to all riders, with whites sitting from the front to the back and African Americans sitting from the back to the front. The boycott served as a model for the Montgomery Bus Boycott two years later.

Free carpools were set up to support the Baton Rouge boycott. The free-ride network created in Baton Rouge was also copied in Montgomery.

The Tallahassee Bus Boycott

Florida A&M student Morris Thomas refuses to move to the back of the bus

Tallahassee carpool station

Boycott leaders ride a bus in Tallahassee, Florida

In May 1956, police arrested two Florida A&M students, Wilhelmina Jakes and Carrie Patterson, for sitting in the front of a city bus. Soon after, Rev. C. K. Steele created the Inter-Civic Council (ICC) to organize a bus boycott.

When the Supreme Court outlawed bus segregation later that year, the ICC suspended its boycott. But white riders threatened violence against Black riders sitting in open seats, and Florida’s governor suspended bus service. After a ruling by a federal judge, integrated bus service resumed in January 1957.