Community Story

Pullman Porters and Maids

Train Travel and the Pullman Palace Car Company

Illustrated promotional booklet, "Go Pullman," issued by the Pullman Company

Newspaper advertisement for the Pullman Company featuring "A Pullman Captain and his Crew"

In 1862, the federal government funded the expansion of the railroad system to connect the Atlantic and Pacific coasts. Trains were faster than horse-drawn carriages and became the preferred way to travel long distances. Though faster, train cars could be overcrowded and uncomfortable.

In 1867, George Pullman started the Pullman Palace Car Company to provide a luxurious experience for train passengers through comfortable accommodations and impeccable customer service. The company became known for its “sleeping cars,” which allowed passengers to rest in beds during overnight trips. The Pullman Company also became known for the service its porters and maids provided.

Pullman, a white man, hired formerly enslaved African Americans for these positions because he felt they would be deferential and service-oriented.

Life of a Pullman Porter

Pullman porter loading luggage onto a train

Pullman porter preparing an upper berth in a train sleeping car

Pullman porters made beds, carried baggage, served food and drinks, shined shoes, and catered to other passenger needs. As trains traveled across the country, porters were responsible for everything that occurred on the railcar.

Porters worked day and night as trains traveled from city to city. They worked long hours for low wages and relied on tips from passengers. They were also responsible for buying their own uniforms and supplies. Porters were required to maintain a pleasant demeanor when subjected to racism and disrespect. They were often referred to as “George” (after George Pullman, the company’s founder) instead of their real names.

Despite low pay, porters still earned more money than most jobs available to African Americans at the time. Pullman porter jobs were desirable and highly respected in African American communities.

Pullman Step Stool

Step stool used by the Pullman Palace Car Company

Explore the step stool to learn more about the duties and working conditions of Pullman porters.

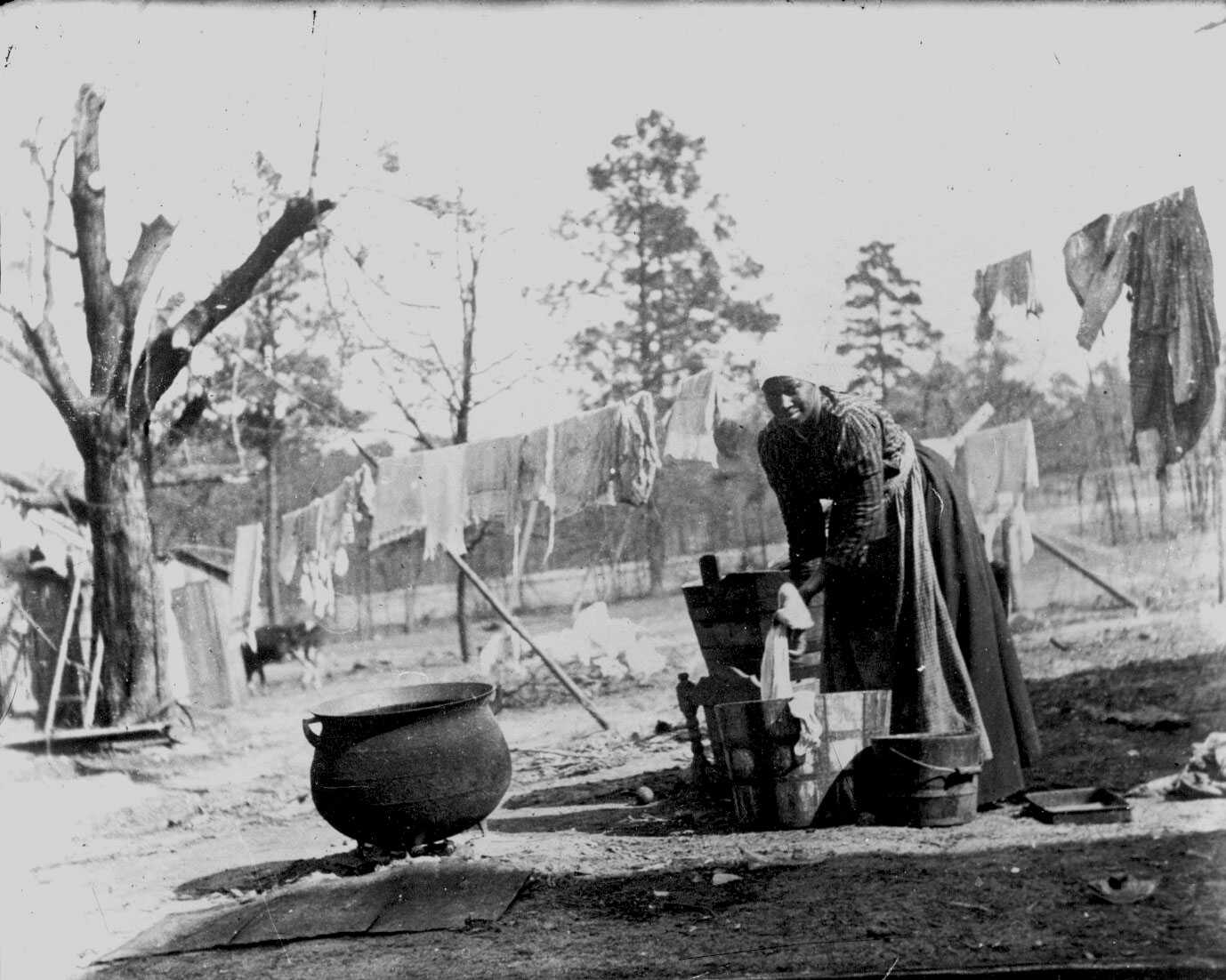

Life as a Pullman Maid

Ruby, a Pullman maid, with a young girl

Pullman maids provided childcare, took care of sick passengers, and attended to female passengers as they bathed and dressed. They also did manicures for male and female passengers. While a team of porters was assigned to each train, only one maid was assigned per train.

Like porters, Pullman maids were at the mercy of train schedules and were required to work from city to city with little time off and without pay for delays or illness. They were also required to buy their own uniforms.

In addition to facing racial discrimination, the maids were sometimes sexually harassed by male passengers.

The first year that I went into the Pullman service, you called it ‘running wild.’ That is, wherever there is a need for a maid, you were to go. On the Overland [route], it may have been the maid was sick and I would have to take her place. If I got into Chicago and there was an emergency for a maid on the Twentieth Century, I would have to go. In New York, when I got there, they needed the service of a maid who was off, or something happened going somewhere else I was to go.

Francis Albrier, civil rights activist, 1977

Front of Mary Harris’s identification card

Mary Harris worked as a Pullman maid in the Chicago region. The front of her identification card features her age, height, and weight.

Back of Mary Harris’s identification card

Mary Harris’s photograph is stapled to the back of her identification card.

Creating the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and Maids

By the 1920s, the Pullman Company employed more African Americans than any other company in the United States. Pullman employees began demanding stabilized pay, set work hours, and dignified treatment.

Labor activist A. Philip Randolph helped Pullman employees establish the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and Maids in 1925. It was the first Black union. Because Randolph was not a Pullman employee, he could organize without fear of retaliation from the company. The union represented porters, maids, busboys, and attendants.

In 1937, the Brotherhood successfully negotiated a new contract with the Pullman Company that provided better work conditions and protections.

| Before Union | After Union | |

|---|---|---|

Worked up to 400 hours a month | Work up to 240 hours a month | |

Little to no paid vacation days | Twelve paid vacation days | |

Low pay supplemented by passenger tips | Standard monthly pay rates for porters, maids, bus boys, and attendants | |

No guaranteed time to sleep on long shifts and overnight trips | Guaranteed 3 to 4 hours of sleep on trips 12 or more hours | |

No protections against unjust treatment or punishment from supervisors | Employees could file grievances and dispute claims made against them |

International Convention of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and Maids, 1937

Porters Featured in

Pullman porters were featured in the 1935 film, Journey By Train. Though no copies of the film exist today, the National Museum of African American History and Culture owns the only known photographs used to promote the film. These images depict Pullman porters at work.

Pullman Employees and the Black Middle Class

Organ belonging to Pullman porter Henry Long, 1911

Pullman porter Omer Ester and his wife, Jean

Pullman porters were highly respected in African American communities before and after the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was founded. Despite difficult schedules and low wages, their families were able to purchase homes, invest in their children’s educations, travel for pleasure, and enjoy leisure time. The salaries, social connections, and steady work for Pullman porters and maids supported the growth of the Black middle class.

The Legacy of Pullman Porters and Maids

Frances Albrier, 1942

Through their travels, Pullman porters and maids brought Black newspapers like the Chicago Defender to African American communities around the country. The networks they created helped spread the word about issues, events, and organizing efforts during the fight for civil rights. Many Pullman employees like Thurgood Marshall, Malcolm X, and Frances Albrier went on to become prominent activists in the modern Civil Rights Movement.

As more Americans bought cars, train travel declined and the need for porters, maids, and other train workers decreased. In 1978, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters merged with what is now called the Transportation Communications International Union.

Freedom is never granted; it is won. Justice is never given; it is exacted. Freedom and justice must be struggled for by the oppressed of all lands and races, and the struggle must be continuous . . .

A. Philip Randolph, 1940