Chapter 3

Protesting and Marching for Civil Rights

African Americans resisted segregation through individual and collective action. Privately, they attended to their families, their communities, and their lives. Publicly, they boycotted, marched, and protested, forcing businesses and cities to desegregate.

Organizations such as the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) provided training and funding for desegregation efforts.

Desegregating “With All Deliberate Speed”

In 1954, the Supreme Court ruled that segregated education was unconstitutional and ordered schools to desegregate “with all deliberate speed.” But across the South, governments and school systems resisted integration. White families moved their children to private schools, while hostile mobs confronted African American children who tried to enter white schools.

The Little Rock Nine

The Little Rock Nine with Daisy Bates, 1957

In 1957 Daisy Bates, president of the Arkansas NAACP, selected nine students to integrate Little Rock Central High School. But on the first day of classes, Governor Orval Faubus ordered the Arkansas National Guard to keep the students from entering the school. At the urging of Martin Luther King Jr., President Dwight Eisenhower reluctantly federalized the Arkansas National Guard and sent in the Army’s 101st Airborne to assist in escorting the students to school. Despite harassment from their classmates, all but one of the Little Rock Nine finished the school year. One of the students, Ernest Green, became the first African American to graduate from Little Rock Central High School.

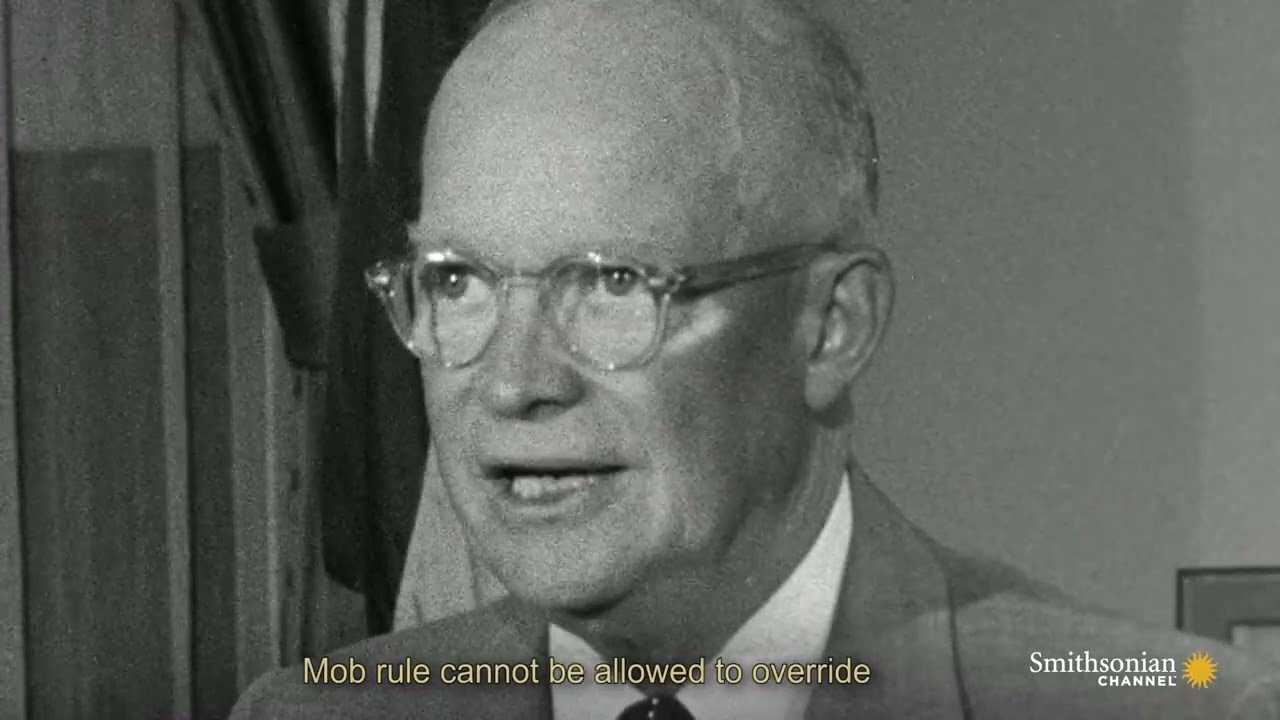

Featured Video

Desegregation in Little Rock

The fight over segregation in Little Rock, Arkansas, made national and international news when President Dwight Eisenhower sent federal troops to enforce the desegregation of Central High School. This video captures the drama of the confrontation, in which Black students faced menacing crowds and harassment.

Carlotta Walls LaNier

Age 14

Carlotta Walls LaNier’s 10th-grade report card

Carlotta Walls LaNier’s skirt and blouse

Graduation picture of Carlotta Walls LaNier

Carlotta Walls LaNier was the youngest student chosen to integrate Little Rock Central High School in 1957. Though her family was threatened and students taunted her, she continued her studies. The following year, when the governor closed all Little Rock public high schools, she took a correspondence course to stay on schedule. After schools reopened, she became the first female African American student to graduate from Little Rock Central High School Her family’s home was bombed shortly before her graduation.

I thought after a few days of ranting and raving, it would all be over. So I was not afraid. I just wanted to go to my neighborhood school, a school I passed every day on the way to my own.

Carlotta Walls LaNier

Daisy Bates and the Little Rock Nine

Daisy Bates with Little Rock Central High School students

Daisy Lee Gatson Bates, newspaperwoman

Daisy Bates was president of the Arkansas NAACP, and her house was a meeting place for integration supporters. Bates helped select the students who would desegregate Little Rock High School, and she supported and counseled them once they began their school year. Later, Bates was elected to the executive council of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

Dorothy Geraldine Counts

Age 15

Dorothy Geraldine Counts

In 1957, Dorothy Counts and three other teens were selected to integrate Harding High School in Charlotte, North Carolina. On the first day of school, an angry crowd of white students and adults greeted the Black students with jeers and racial slurs and threw sticks and stones. In school, Counts was taunted by other students and her family received death threats. Local police claimed they could not guarantee her safety, and after four days her parents withdrew her from Harding, sending her to a school in Philadelphia instead.

Ruby Bridges

Age 6

Ruby Bridges at home

U.S marshals escorting Ruby Bridges from school

In 1960, Ruby Bridges was one of six African American children chosen to integrate New Orleans’s all-white elementary schools. After local officials refused to protect her, four U.S. marshals escorted Ruby and her mother to William Frantz Elementary School. Only one teacher agreed to teach her, and Ruby Bridges had to be in a class by herself. Though her father was fired from his job and her grandparents were forced from the farm they rented, Ruby Bridges finished the school year and stayed at William Frantz throughout elementary school.