Visions of Freedom: Community

During Reconstruction, formerly enslaved African Americans expressed their freedom by taking control of their own educational, religious, economic, and social lives. Independent institutions, including churches, schools, businesses, and associations, provided infrastructure for African American communities and refuge from white oppression. They also served as bases for political activism and leadership training.

Education During Reconstruction

Zion School, 1866

Of all the things freedom signified to newly freed people, the right to educate themselves and their children was one of the most prized. The right to read and write, denied to African Americans who were enslaved, represented independence, opportunity, and the power to fully participate in the political, economic, and religious affairs of the community. During Reconstruction, access to education became a key measure of African American progress toward equal citizenship.

It was a hard thing having to build that school for the white boys when I had no right to educate my son. Then when the war was over and they bought that building for our children, I could hardly believe my eyes—looking at my own little ones carrying their books under their arms, coming from the same school the Lord really raised up for them.

Ambrose Headen, recalling the establishment of a freedmen’s school in Talladega, Alabama

Freedmen’s School, South Carolina, 1862

Freedmen’s Schools

Education Among the Freedmen

Friends Freedmen’s Association Teachers, Norfolk, Virginia, 1863

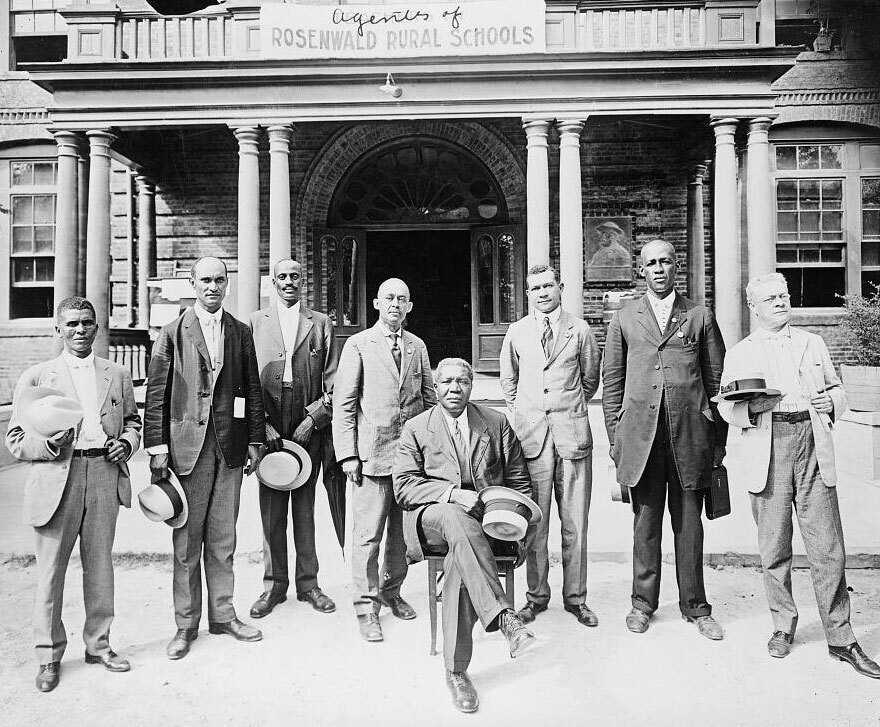

As freedom spread across the South during the Civil War, demand for schools followed. The first “freedmen’s schools,” which educated girls and boys as well as adults, were established by northern missionaries in areas occupied by the U.S. Army. After the war, newly freed people began building their own community schools, often as part of churches, with teachers and supplies provided by the Freedmen’s Bureau and northern aid societies.

Targets for Terrorism

Freedmen’s Affairs in Kentucky and Tennessee

While a few white southerners supported the establishment of schools for newly freed African Americans, many more reacted with hostility and violence. White terrorists threatened and attacked teachers and students, burned down schoolhouses and Black churches, and intimidated Black businesses and communities.

Burning a Freedmen’s School-House, Memphis, Tennessee, 1866

Twice I have been shot at in my room. . . But I trust fearlessly in God and am safe.

Edmonia G. Highgate, 1866

Free Schools for All

Revised Code of Mississippi, 1871

During Reconstruction, African Americans led the movement to make public education a right not only for themselves, but for all citizens. Black politicians elected to state and local governments helped pass legislation to establish the first public school systems in the South. Although most public schools were segregated and became increasingly unequal over time, they were founded on the principle that every child, Black and white, had an equal right to an education.

We young ladies of Wilberforce are here to improve our minds, to become intelligent women, to prepare ourselves to go forth into the world . . . We are like the busy bee, always seeking, always endeavoring to elevate our race.

Zelia R. Ball, 1874

Higher Education

First graduating class of Spelman College, Atlanta, Georgia, 1887

Otis Shackleford’s graduate profile in What the Graduates of Lincoln Institute Are Doing

The first Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) in the South were founded during Reconstruction. Their primary purpose was to provide a supply of highly trained Black teachers for the new public schools opening up to educate Black children. Many of the men and women who graduated from Black colleges and universities during this era became not only effective classroom educators but also leading members of their communities and activists for social justice.

Storer College

Storer College students and teachers, ca. 1870

Telescope from Storer College

In 1865, Free Will Baptist missionaries from New England established a freedmen’s school in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. With support from Maine philanthropist John Storer, the school became Storer College. It opened in 1867 with 19 students and offered high school as well as college education. Until 1891, it was the only teacher-training institution for African Americans in West Virginia. The college continued to operate until 1955.

The Value of Education

During the era of segregation, African Americans continued to pursue higher education by creating institutions now referred to as Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs).