Chapter 2

Revolutionary War

From their earliest forced arrival in colonial North America, enslaved Africans had rebelled. Crispus Attucks, a 47-year-old sailor and fugitive enslaved man, became the first casualty in the Boston Massacre, and his act of defiance marked the beginning of the march towards revolution. By April 1775, Massachusetts militiamen clashed with British troops, launching the Revolutionary War.

The conflict touched everyone—white, Black, enslaved, or free. With much of colonial society built on human bondage, some felt that there was a paradox at the heart of the American Revolution. Abigail Adams, a white Patriot, wrote: “It allways appeard a most iniquitious Scheme to me—fight ourselves for what we are daily robbing and plundering from those who have as good a right to freedom as we have.” For Africans, the Revolution was a battle for freedom from slavery.

Africans, at 20% of the colonial population, could tip the scales of war and therefore could not be ignored. The British and Colonial armies, initially reluctant, sought the advantage of recruiting able-bodied enslaved African men to support their cause. Africans aligned with whichever side offered the better promise of freedom. Black Patriot Boyrereau Brinch remembered: “Thus was I, a slave for five years, fighting for liberty.”

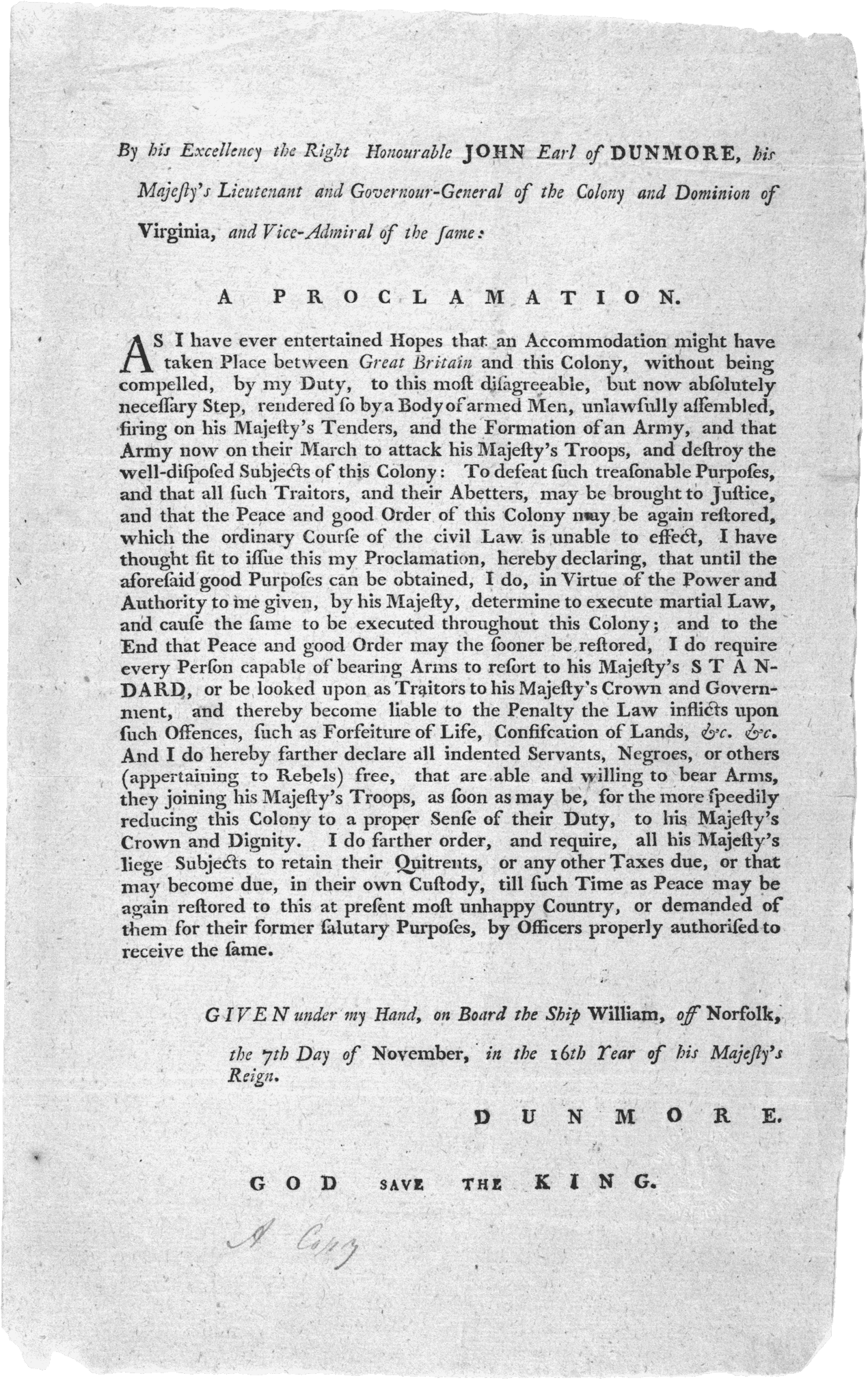

Dunmore’s Proclamation

Lord Dunmore's Proclamation

In November 1775 the Royal Governor of Virginia John Murray, the Earl of Dunmore, issued a proclamation that offered freedom to "all [indentured] servants, Negroes, or others . . . that are able and willing to bear Arms" for the Crown. But this promise was not fulfilled after the war, and Black people enslaved by Loyalists were returned to enslavement. Of those who fled from Patriot enslavers to British lines, some eventually secured their freedom and others were enslaved in the West Indies.

Patriot Patrick Henry, who declared "give me liberty or give me death," considered Lord Dunmore a traitor for offering freedom to enslaved people who fought under the Crown.

Ethiopian Regiment

The Death of Major Peirson

Revolutionary War-Era Musket

By 1775 the British in Virginia had 300 formerly enslaved people fighting on their side. In uniform, they wore sashes bearing the words, Liberty to Slaves. These Black men were known as Lord Dunmore’s Ethiopian Regiment. Fearful of the growing number of Black Loyalists, Patriots quickly reminded enslaved people that the British originated slavery in the British colonies. The Ethiopian Regiment saw combat but served only a short time before many of its members succumbed to a smallpox epidemic.

Black Loyalists

Certificate of Freedom Issued to Cato, a Black Loyalist

Armed with the promise of freedom for service by the British, enslaved Black people rebelled against the system of slavery and fought for their own liberation. By the end of the war, they eagerly awaited passage beyond the border of the enslaving nation. Against the protestations of George Washington, British Brig. Gen. Birch issued certificates of freedom to Black Loyalists to depart for freedom in the British colonies. It is estimated at least 20,000 enslaved people, over half from the South, fled to join the British from 1775 to 1782.

At the end of the war some secured their freedom and others were sold back into slavery, but all challenged the limits of liberty.