Slavery and Freedom in Charleston

Charleston, South Carolina, 1851

At least 40% of enslaved African people brought to Colonial North America were imported through ports in South Carolina. The colony became wealthy and powerful from the sale of enslaved Black people and the products of their labor. In Charleston, some enslavers increased their profits by leasing (hiring out) people they enslaved. Enslavers who hired out their enslaved workforce were required to register them with the local government. The Charleston slave badge system ensured that enslaved laborers who were hired out could not pass as free Black people.

Like other colonies, South Carolina included free Black populations. The badge system required free Black people to register their status and wear a free badge. Whether enslaved or free, Black people were under constant surveillance and government regulation.

No owner or other persons having the care and government of negroes or other slaves, shall permit any such slave, to be employed on hire, out of their respective houses or families without a ticket or badge first had and obtained from the Corporation of this City.

An Act to Incorporate Charleston, 1783

Charleston’s Slave Badge Laws

Charleston slave badge for Porter No. 165, 1805

Announcement of slave badges for the year 1805

As early as 1690, enslavers began hiring out enslaved people – leasing them to others to perform specific work. Leasing was normally used for skilled tradesman who worked as carpenters, mechanics, brick masons, blacksmiths, porters, fishermen, fruiters, and others. In 1783 a new law required enslavers to register hired-out enslaved persons with the Corporation of the City. Enslavers had to pay a fee to the City Treasurer and secure a ticket or badge indicating everyone’s name, place of origin, and destination. In 1786 the law required badges to be worn. It stated that “Every Negro working out on hire, shall wear the Badge received from the City Clerk on some visible part of their dress . . .”

Who Profited?

South Carolina hiring agreement for an enslaved woman named Martha, 1858

Almost everyone benefited from hiring out enslaved laborers. Enslavers collected wages enslaved people earned from their labor Business owners reduced costs by hiring enslaved laborers. Charleston’s government received funds from registration fees, taxes, and non-compliance fines.

Additionally, local residents reaped the benefits of the city’s infrastructure built by leased enslaved labors. Hired-out brick masons, blacksmiths and other skilled artisans paved Charleston’s roads, constructed its buildings, and built its infrastructure projects. Enslaved laborers even worked for the fire department.

Black Agency

Enslaved family in South Carolina

Enslaved Black people hired out by their enslavers were separated from their own families and communities. They faced uncertain and potentially dangerous work environments.

Hired-out enslaved people had a limited degree of agency. They were able to expand their networks and learn about efforts towards freedom. Some enslaved African Americans kept wages from hired-out arrangements. This allowed them to save money to purchase freedom for themselves and their loved ones.

A Tool for Surveillance

Runaway ad for Mary, a washerwoman with badge no. 471

Slave badges served as identifiers. They were stamped with “Charleston,” the badge number, the enslaved laborer’s occupation, and the issuing year. Enslaved laborers were required to sew the badges onto their clothing, and all badges had to be reissued each year. When an enslaved person ran away, the badges were used in runaway ads used to locate them. Enslaved laborers, craftsmen, and artisans were documented, verified, and marked. The badge system was a form of surveillance that regulated leased labor and restricted Black mobility.

Negro girl CLARINDA about 17 years of age... and well known in this city. She was bought from the estate of Axon...has badge No. 176.

Charleston Courier, 1822

Acquiring the Historic Collection

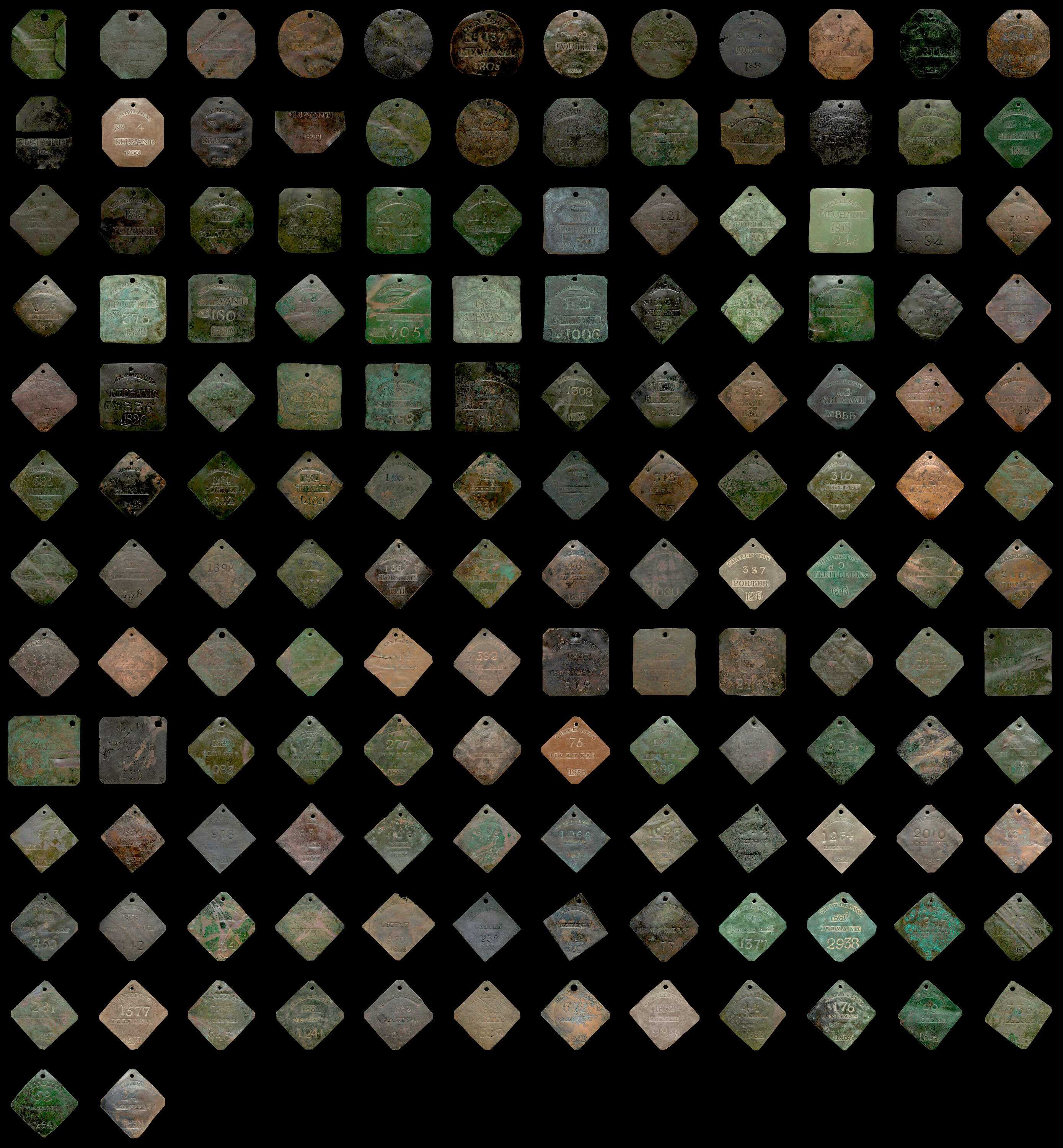

Charleston Slave Hire Badge Collection

In 2022, the National Museum of African American History and Culture acquired a rare collection of 146 Charleston slave badges. The collection is the only known complete set of slave badges. It includes a badge from each year between 1800 and 1865 and contains the only two badges that name an enslaved person. Collector Harry S. Hutchins, Jr. dug up, compiled, and preserved the badge collection over thirty years. When presented with the opportunity to draft the credit line for the collection, Hutchins provided the following text “Partial Gift of Harry S. Hutchins, Jr. DDS, Col. (Ret.) and his Family, dedicated to the individuals these Slave Hire Badges represent and their descendants.” The Museum will use the badges to honor the legacies of the men and women who endured slavery.

The Charleston Slave Hire Badge Collection

8 of the 146 badges in the collection.

Uncovering History

Archaeologist Alexandra Jones (center) with students

Archaeology is the study of human cultures through objects or remains excavated from the ground or underwater. It helps us understand more about the brutality of the system of slavery and what enslaved African Americans endured, as well as what they contributed to society.

The law required that new slave badges were issued every year. Outdated badges were often randomly discarded and badges have been found on former plantation sites and at construction sites in downtown Charleston. In 2021, an 1853 slave badge was excavated during a cultural survey conducted on the College of Charleston campus. The historic find helps historians further understand the College’s connections to slavery and the contributions of enslaved African Americans to the institution.

Authenticating the Slave Badges

1802 Charleston slave badge for Porter No. 116

The Smithsonian uses historical research to authenticate objects in its collections. In the late 1900s, the value of slave badges on the slave memorabilia market increased dramatically. As a result, many forgeries have been created. Harry Hutchins Jr. and archivist Harlan Greene co-authored Slave Badges and the Slave-Hire System in Charleston, South Carolina: 1783-1865. Their book is considered one of the authoritative publications on the history of Charleston slave badges and provides information on how to authenticate badges. Additionally, the scholarship of historian Bernard Powers and archaeologist Theresa Singleton provide insight into the history and relevance of slave badges.

The Smithsonian uses scientific data to authenticate badges. Conservators – those who preserve and repair objects – use x-ray technology to determine the objects’ composition and date the age of purported historic objects. These efforts help authenticate collections, assist with preservation efforts, and identify forgeries.

Why the Slave Badges Matter

Isaac Granger Jefferson, Enslaved Blacksmith, ca. 1845

Charleston slave badges reveal that many African Americans were valued for their skills, craftsmanship, and knowledge. The badges also shed light on the conditions of urban slavery in and around Charleston. Though the individuals who wore them are no longer here, the Charleston slave badges bear witness to a community of laborers and artisans who held on to their humanity despite inhumane conditions. They left their mark as they created the historic Charleston landscape.

Looking at a slave badge evokes an emotional reaction. There is the realization that one person actually owned another.

Professor James O. Horton, George Washington University, 2003