Chapter 4

Pushing for Permanent Change

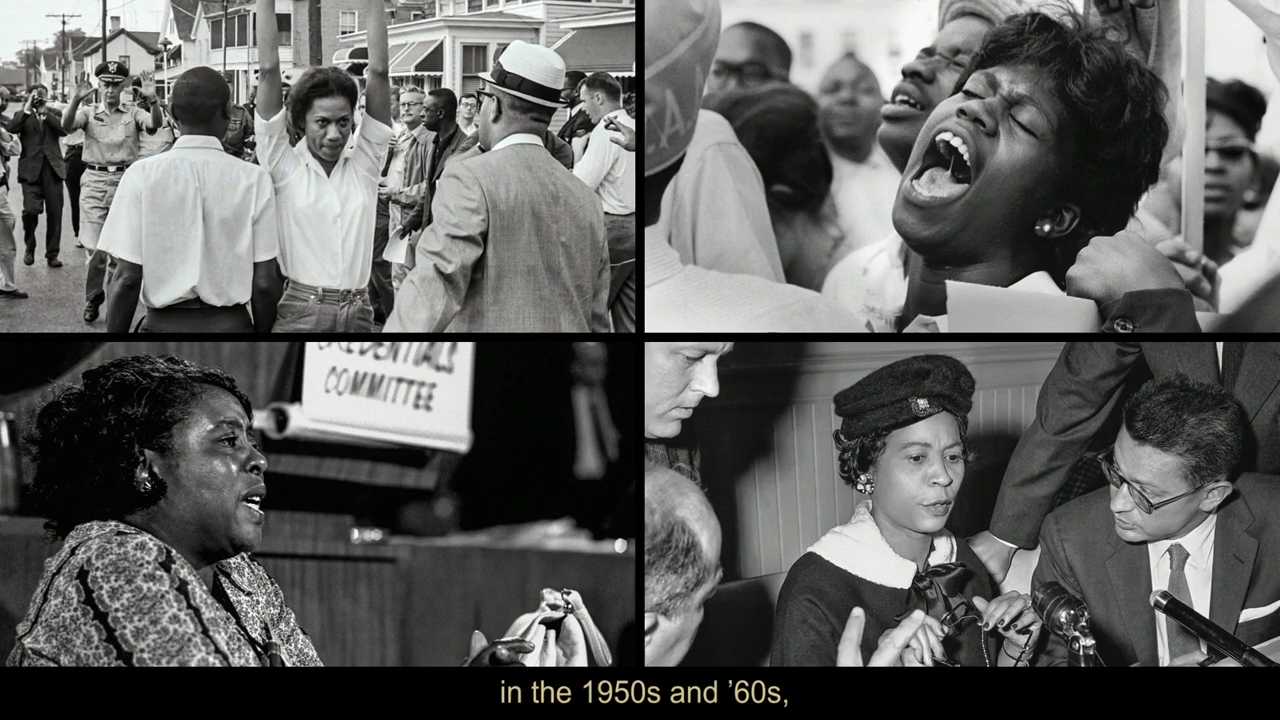

African Americans, along with their allies, pushed to secure civil rights by changing America’s laws. Through large demonstrations and marches, activists brought the nation’s attention to the struggle for civil rights and full citizenship.

But some younger African Americans wanted more direct results. Frustrated by the slow, gradual change of the Civil Rights Movement, they looked to the Black Power Movement and its demands for immediate equality.

What Was the March on Washington?

Marchers at the Lincoln Memorial

In 1963, civil rights leaders A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin began plans for a march on Washington to protest segregation, unemployment, and the lack of voting rights for African Americans. Randolph and Rustin enlisted the support of every major civil rights organization. The march took place on August 28, 1963.

The interracial group of presenters for the day included representatives from each planning organization. Martin Luther King Jr., leader of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, delivered his famous “I Have A Dream” speech.

Purpose of the March

Women participating in the March on Washington

March organizers Bayard Rustin and Cleveland Robinson

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom sought new civil rights laws and protections that would desegregate public accommodations, end discrimination in housing, education, employment, and voting, and enforce the Constitution’s guarantee of equality for all under the law.

The Murder of Medgar Evers

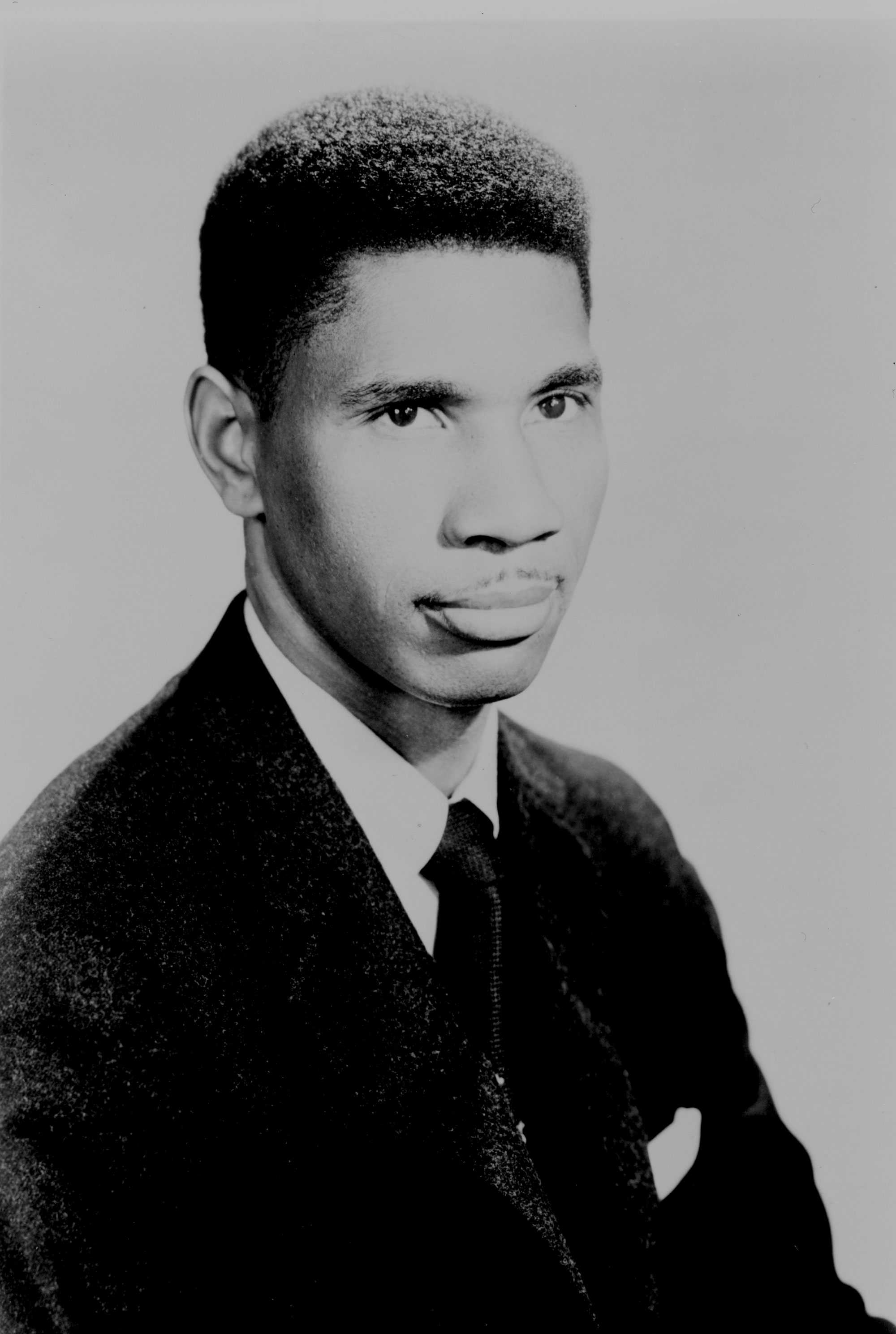

Medgar Evers was the first major civil rights leader assassinated in the 1960s.

Myrlie Evers, with her children, views the body of her husband Medgar Evers.

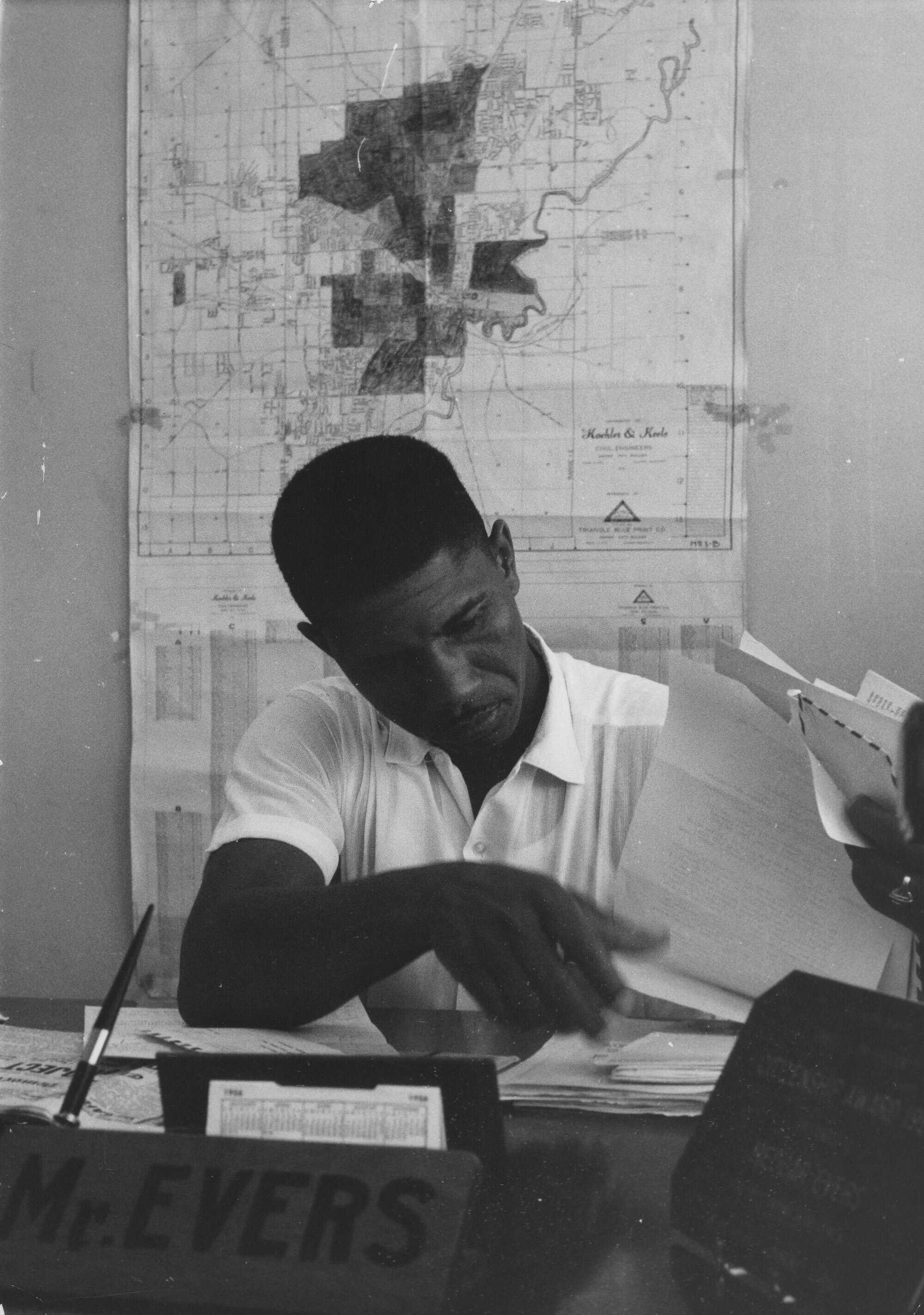

As field secretary for the Mississippi NAACP, Medgar Evers traveled the state investigating acts of violence and intimidation. He also organized voter registration drives, economic boycotts, and civil rights demonstrations. On June 12, 1963, Evers was shot in his driveway as he walked towards his home. His accused killer, Byron de la Beckwith Jr., remained free until 1994, when he was finally convicted of Evers’s murder.

Evers was the first major civil rights leader assassinated in the 1960s. His June 1963 death prompted angry protests and added urgency to the planning for the March on Washington in August.

Featured Story

Medgar Evers

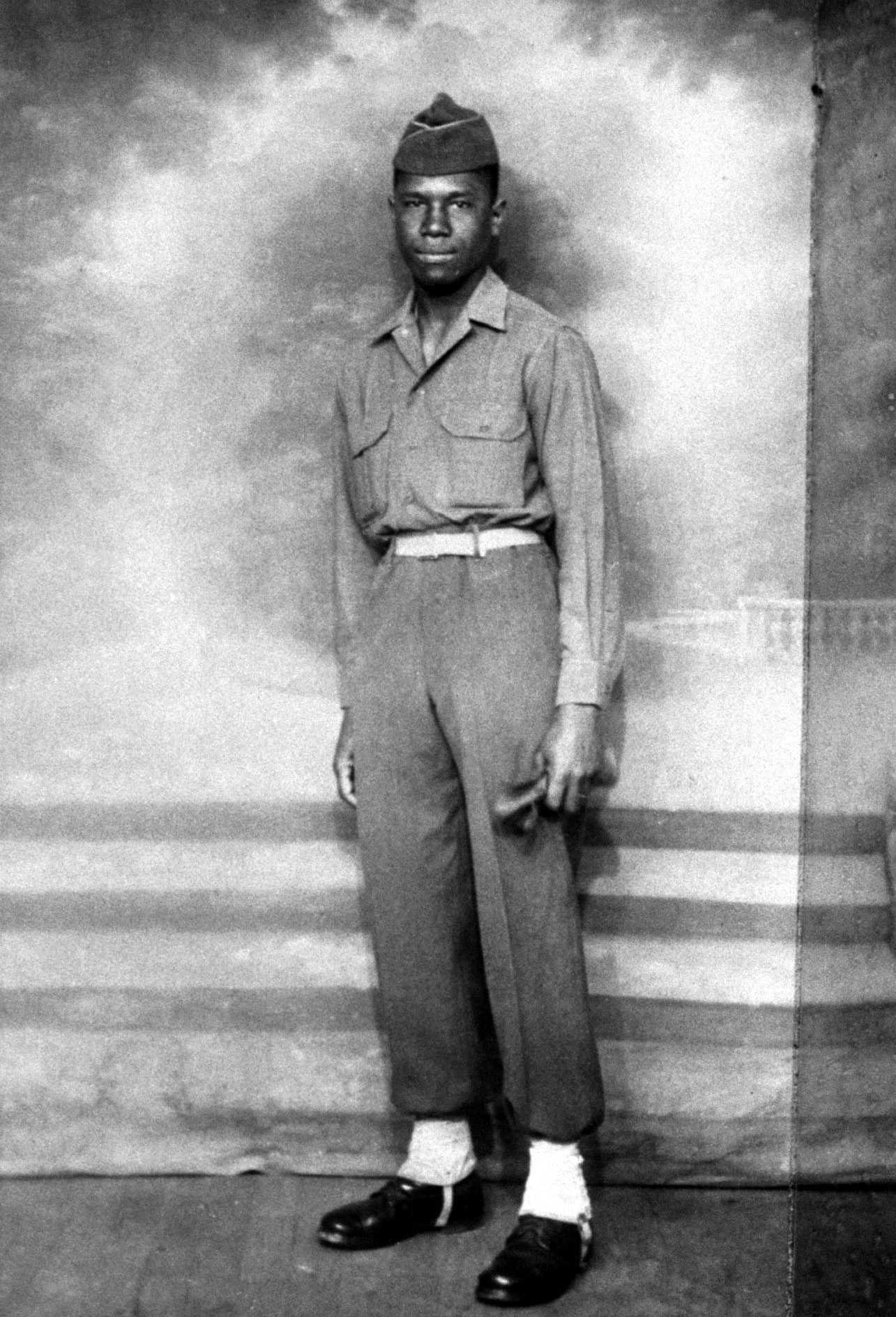

Medgar Evers was a World War II veteran who became an NAACP leader and civil rights activist in his home state of Mississippi.

Marching for Jobs and Freedom

An interracial crowd of 250,000 gathered and listened to speakers.

Featured Document

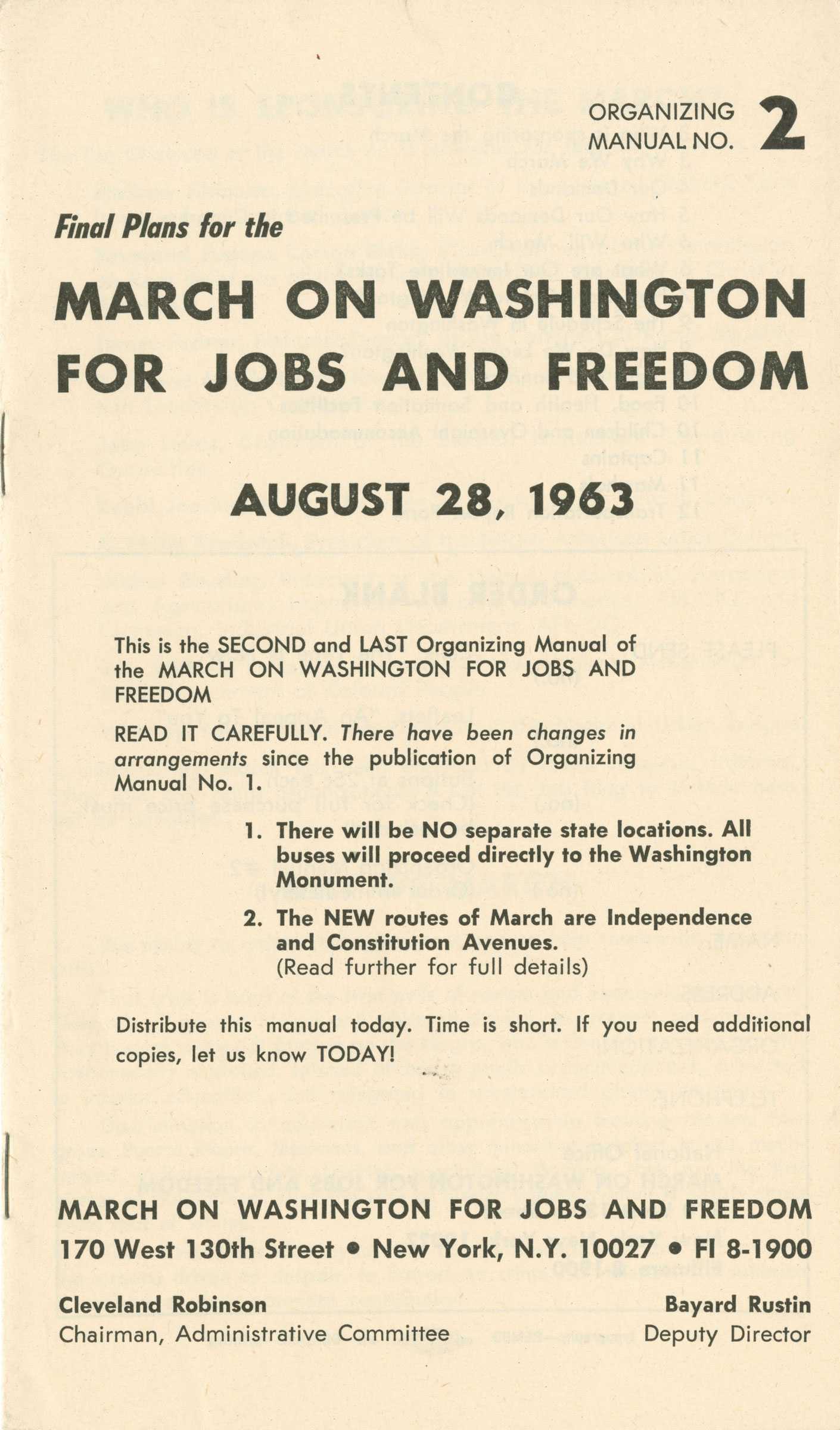

March on Washington Organizing Manual

A march of this size required massive coordination. Participants needed travel plans, food, sanitation, and medical care.

Planning the march required massive organizing. Organizers coordinated transportation to and from the march. Planners also managed logistics for food, sanitation, and medical services. Lead organizers Bayard Rustin and Cleveland Robinson created this manual to share important information, define the march’s purpose, and list their demands to Congress.

March Speakers

Josephine Baker at the March on Washington

A series of prominent civil rights leaders gave speeches at the March on Washington, including A. Philip Randolph, James Farmer, Whitney Young, and John Lewis. Despite the important work of women activists and organizers, Josephine Baker, Rosa Parks, and Daisy Bates were the only women who addressed the crowd. Known for her efforts to desegregate schools in Little Rock, Bates read the “Tribute to Women” written by march organizers.

Bayard Rustin, Activist

Bayard Rustin speaking in New York City, 1965

Bayard Rustin was a renowned civil rights strategist. Beginning in the 1930s, he became involved in civil rights activism and peace movements. A Quaker, he disapproved of war, believed in nonviolent resistance, and promoted universal human rights.

As a Black gay man, Rustin experienced racial and sexual discrimination, including prejudice from some civil rights leaders. But Martin Luther King Jr. found him an invaluable advisor. Rustin helped King with the Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1956 and was a key organizer of the March on Washington in 1963. He continued his activism until his death in 1987.

Featured Video

Women and the Movement

Women made significant contributions to the Civil Rights Movement. Learn more about their contributions in this film.