Historic Event

The Power of a Portrait

"I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance"

Carte-de-visite portrait of Frederick Douglass, 1878.

Carte-de-visite portrait of Sojourner Truth, 1864.

African Americans have long claimed self-definition through portraiture. A portrait—a posed image of an individual—allows for memorialization and remembrance. Black people had portraits taken at weddings, funerals, and other key life moments.

From the earliest days of photography, African Americans have used portraiture to promote themselves, argue their causes, and display their humanity. Describing Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth’s ability to understand the “importance of biography through photography,” noted curator and photographer Deborah Willis argues for the centrality of portraiture in the African American imagination. Douglass particularly used his image to promote his message—he became the most photographed American man of the 19th century.

Clothes, like Frederick Douglass’s suits and Sojourner Truth’s bonnets, symbolized respectability and authority. As printed on an 1864 portrait, Truth said that “I sell the shadow to support the substance.” Both recognized the power of photography to support their goal—freedom.

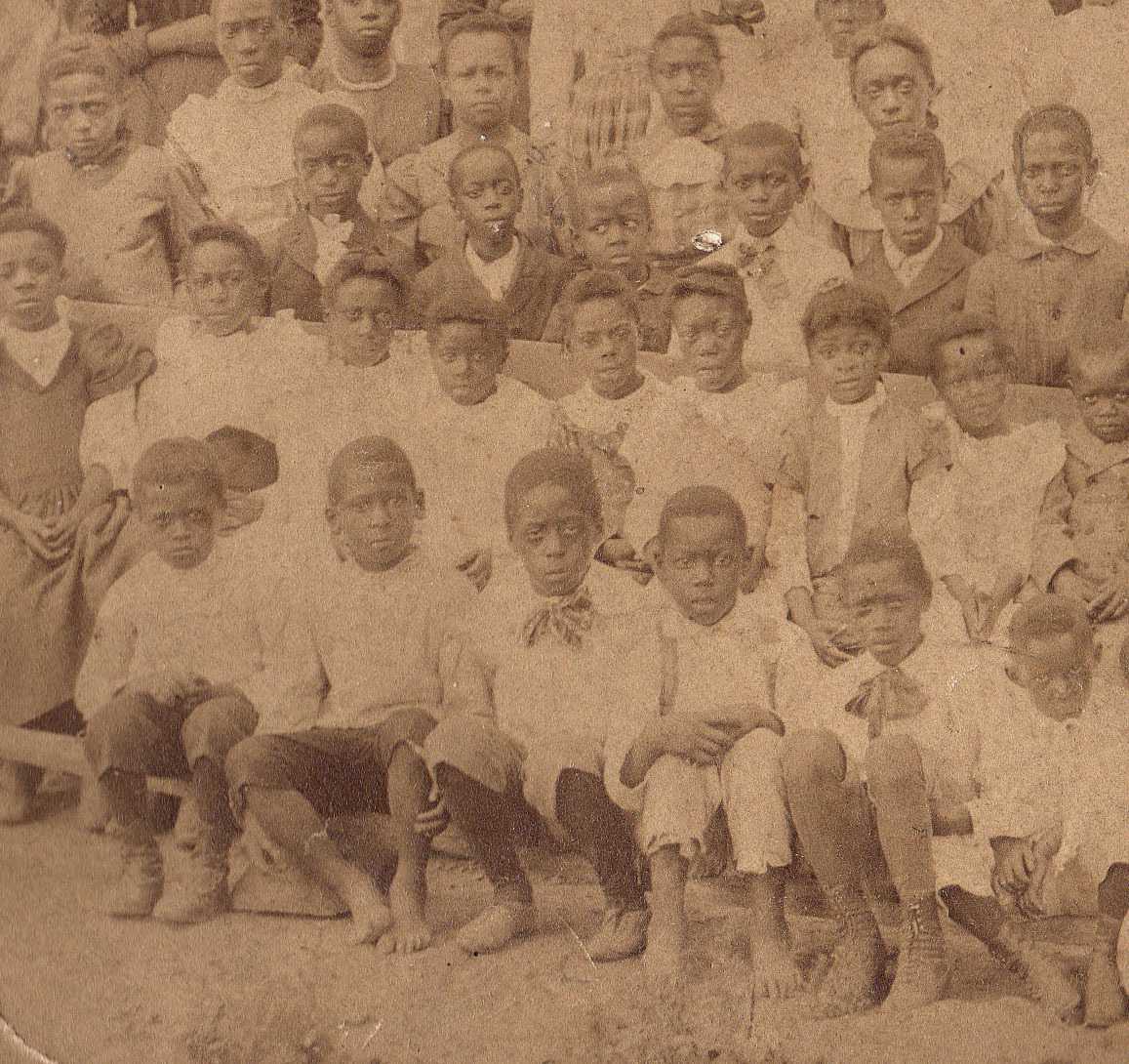

Photographing Black Life

African Americans have created their own images through portrait photography since photography’s invention.

Continuing a Legacy of Portraiture

Photography allows for agency and self-definition, whether in prom portraits or selfies. Contemporary artists like Amy Sherald and Bisa Butler often use photographs as starting points in their artistic process. Inspired by scholars like Deborah Willis and Nell Irvin Painter, Sherald and Butler have transformed photographic portraits into powerful, large-scale works.

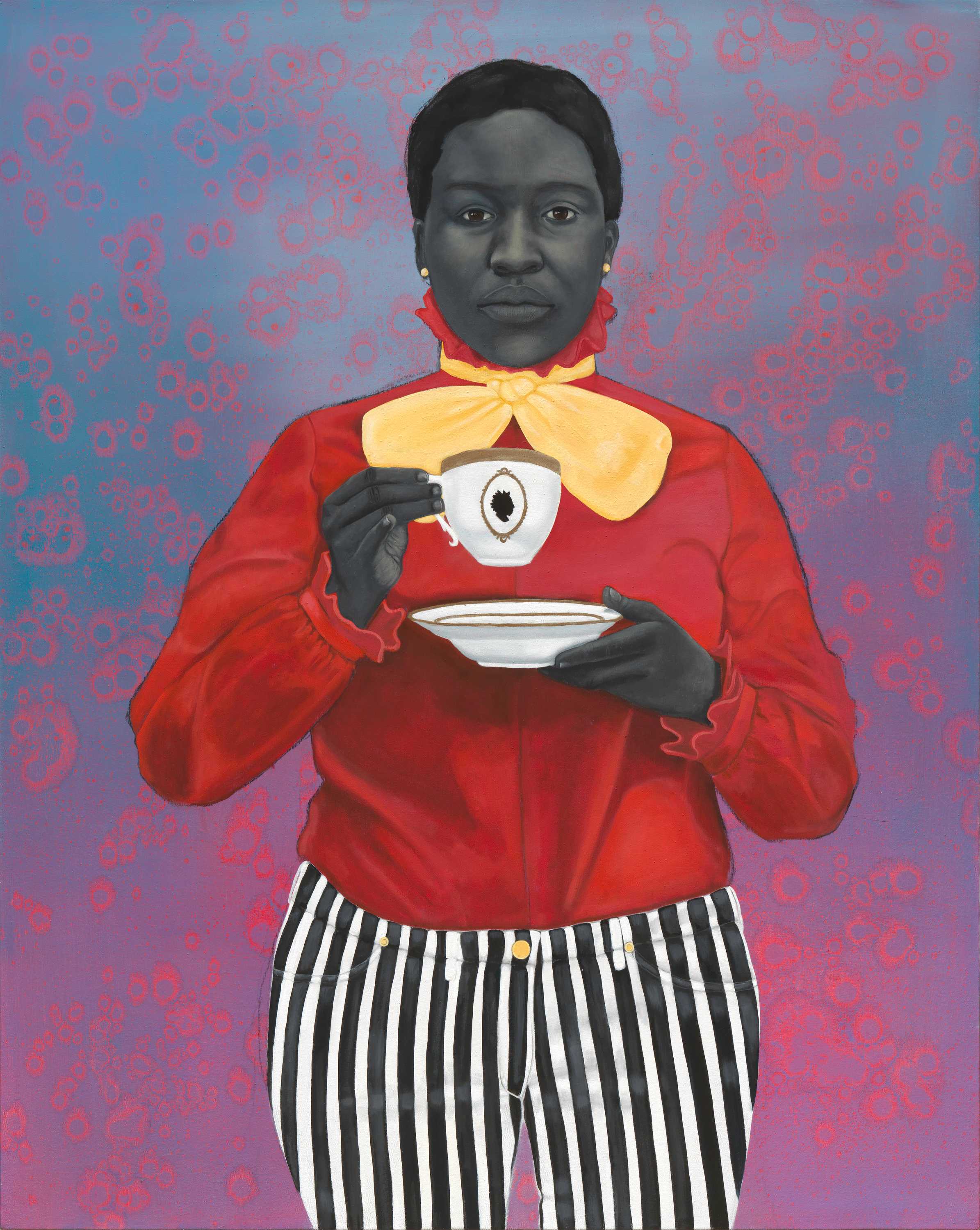

Amy Sherald’s Painted Photographs

Grand Dame Queenie. Amy Sherald, 2012.

Rendered in gray-scale simplicity, Amy Sherald’s portraits contrast bright backgrounds against the Black skin of her subjects. Though Sherald’s artistic process often begins by taking multiple photographs, she had few photos to use for Breonna Taylor’s portrait.

Sherald’s image of Taylor shows different facts of Taylor’s life, including her love of fashion and her love of her partner, shown by an engagement ring. Sherald noted: “I wanted to leave her family with that memory. Not that it can erase the tragedy that happened, but to offer them some kind of solace in the way that she’s represented in the world now."

Breonna Taylor. Amy Sherald, 2021.

Growing up, [photography] was my connection to my past. It wasn’t like I could look at a painting. My family didn’t have painted portraits of ourselves hanging around the house. It was a book of family photographs that I had that really impacted me, and growing up with that gave me a deep sense of self, of dignity, and of how to be, how to become.

Amy Sherald

Bisa Butler’s Quilted Portraits

Don’t Tread on Me, God Damn, Let’s Go! — The Harlem Hellfighters. Bisa Butler, 2021.

Textile artist Bisa Butler creates quilted portraits, often based on photographs. Quilting has a long and rich history among African American craftswomen, and Butler’s textile choices show quilting’s storytelling power. In her portrait of Harriet Tubman, the skirt fabric is designed by Congolese women refugees. Butler’s dark background recalls Tubman’s nighttime journeys spent carrying others to freedom, while sunflowers—a devotional flower—speak to Tubman’s deep Christian faith.

I Go To Prepare A Place For You. Bisa Butler, 2021.

There’s this whole thing about who gets their photos taken, and then who gets to save that photo. And then our family photos, a lot of times, the subject or the person is written about on the back. Or the old photos sometimes had the date, but without that, after you pass a few generations, that information is lost.

Bisa Butler

Featured Video

Portraiture at the Intersection of Art and History: A Conversation with Deborah Willis, Amy Sherald, and Bisa Butler

In this program recorded on March 16, 2023, at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, renowned scholar and artist Dr. Deborah Willis leads a discussion with Amy