Biography

The Remarkable Rollin Sisters

![The inside title page is covered in decorative floral and leaf scroll work. The title reads, [ILLUMINATED / DIARY / for / 1868.]. Underneath is an illustrated image of the sea with a mast ship. The publisher below reads, [PUBLISHED BY / TAGGARD & THOMPSON, No. 29 CORNHILL, / BOSTON.]](/static/969d12bdd7f21bbf9b95dccca084e1de/43eac/Rollin.jpg)

An Elite Upbringing

Artist’s illustration of a street scene in Charleston, South Carolina, 1861

The Rollin family was part of Charleston’s elite free Black community. The sisters’ father, William Rollin, was of French and African descent, from a family that had fled the French colony of Saint-Domingue during the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804). Rollin ran a successful lumber business in Charleston. He employed Irish laborers, many of whom attended the same Catholic church as the Rollin family. Though he could not vote because he was Black, Rollin wielded political influence by controlling the votes of his white workers. He was also a slaveholder.

William Rollin and his wife Margaretta had five daughters: Frances (1845–1901), Charlotte (1847–1928), Katherine (1848–1876), Louisa (ca. 1855–1921), and Florence (1858–1934). The girls received a classical education and attended schools in Philadelphia and Boston. Their experiences in the North exposed them to the abolitionist and women’s rights movements and influenced their future political activism.

After the War

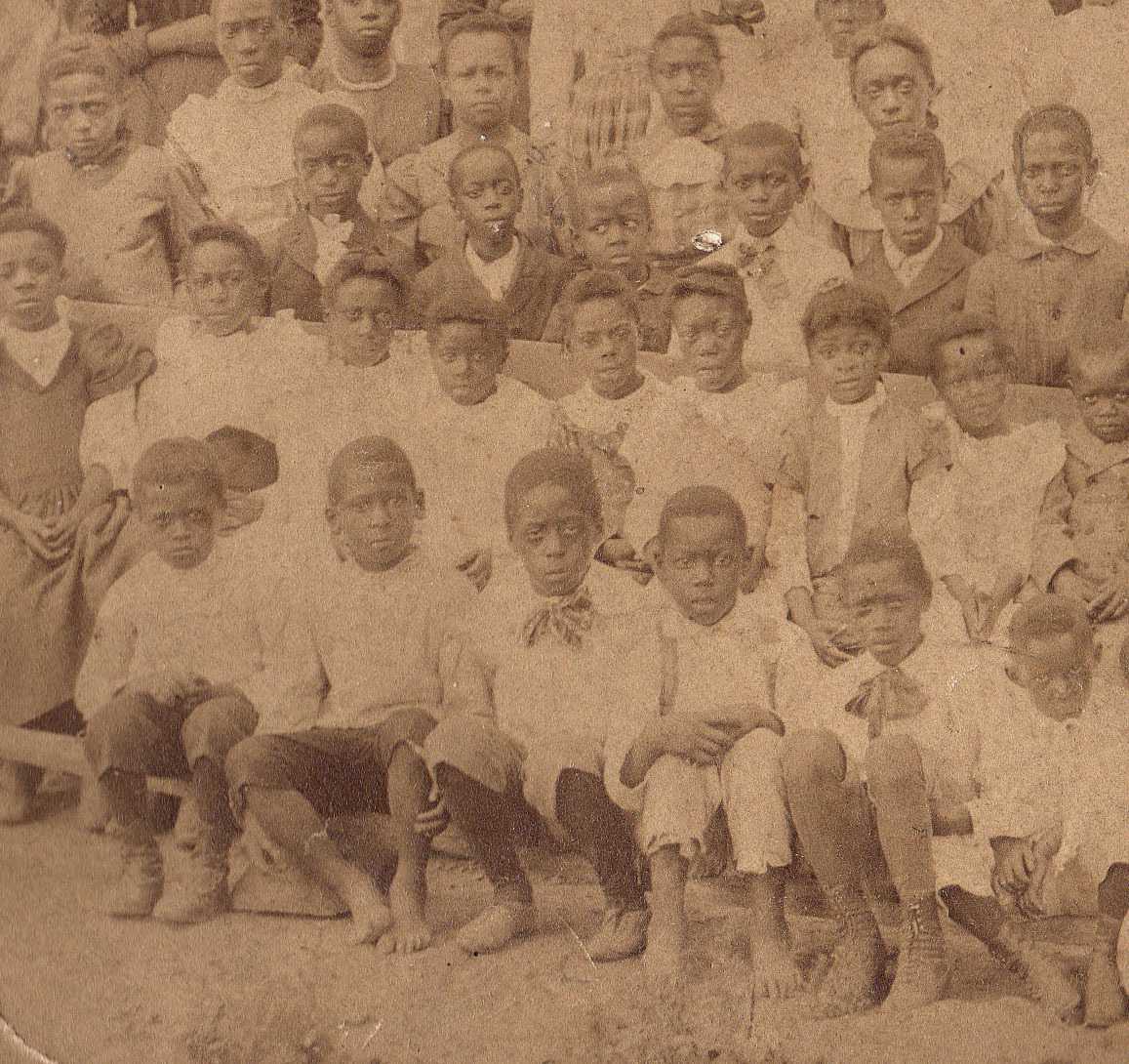

“Zion School for Colored Children, Charleston, South Carolina,” Harper’s Weekly, 1866

The Civil War destroyed William Rollin’s business and left his family in dire financial straits. His three eldest daughters, who had stayed in the North with relatives and friends during the war, returned to South Carolina to support their parents. Like many educated African American women at the time, they became teachers, one of the few professions open to them.

As teachers, the sisters were part of the effort to educate newly freed African Americans in the South. Frances Rollin taught at American Missionary Association schools in Charleston and Beaufort. Charlotte and Katherine Rollin founded a school for African American children in Charleston. After an unsuccessful effort to secure funding from the Catholic Diocese of Charleston, the Rollins moved to Columbia, the state capital, in hopes of establishing another school there. This move brought them into the world of Reconstruction-era politics.

The Rollin Salon

“Radical Members of the South Carolina Legislature,” 1868

The birthplace of the Confederacy, South Carolina was also the center of major political changes that swept through the South after the Civil War. Under the 1867 Reconstruction Acts, Black men in former Confederate states gained the right to vote and hold elected office. In South Carolina, a state with a majority-Black population, voters elected a majority-Black state legislature, the first in the nation’s history.

Through their family’s social and political connections, Charlotte and Katherine Rollin obtained clerkship positions with the new government. At their home in Columbia, located across the street from the State House, the sisters hosted a political salon, where Black and white lawmakers gathered to socialize and discuss the issues of the day. For the Rollins and their allies, the goal was to create a new American democracy—one in which women’s voices would also be heard.

Frances Rollin

Portrait of Frances Anne Rollin Whipper

Life and Public Services of Martin R. Delany by Frank (Frances) A. Rollin, 1868

The eldest of the Rollin sisters, Frances Anne Rollin engaged in the struggle for equal rights as an activist, educator, and author. In 1867, she sued a Charleston steamboat captain for refusing to honor her first-class ticket. She won the lawsuit, which was one of the first to be filed under the new civil rights laws enacted during Reconstruction.

While pursuing her case, Rollin met Maj. Martin Delany, who was working with the Freedmen’s Bureau in Charleston. The renowned abolitionist hired Rollin to write his biography, which was published in 1868. That same year, Rollin married William J. Whipper, a South Carolina state legislator. She continued her educational work, teaching at Avery Institute in Charleston and later in public schools in Washington, D.C.

Diary of Frances Anne Rollin, 1868

We ask suffrage not as a favor, not as a privilege, but as a right based on the ground that we are human beings, and as such, entitled to all human rights.

Charlotte Rollin, address to Woman’s Rights Convention, Columbia, S.C., 1870

Charlotte Rollin

The Woman’s Journal, November 30, 1872

Along with hosting political discussions in her parlor, Charlotte Rollin also spoke out publicly on behalf of women’s rights. In 1869, she became the first woman to address the South Carolina state legislature. In December 1870, Rollin organized a women’s rights convention in Columbia, and in 1872 she served as a delegate to the national convention of the American Woman Suffrage Association.

Working with male lawmakers, including her brother-in-law William J. Whipper, Rollin helped advance legislation for universal suffrage. These efforts culminated in 1872 with a proposed amendment to the state constitution, which would extend the right to vote to “every person, male or female, possessed of the necessary qualifications.” The amendment was rejected, however, and the campaign for women’s suffrage in South Carolina did not regain political momentum until the 1890s.

As for the State of South Carolina, of which we are natives, take my word for it . . . the rebels will never get it back into their hands again while there are ninety thousand votes cast by the Black race at our elections.

Katherine Rollin, 1871

Reconstruction's End

“Of Course He Wants to Vote the Democratic Ticket!” Illustration from Harper’s Weekly, 1876

As southern Black women claiming an equal voice in American democracy, the Rollin sisters exemplified the possibilities that Reconstruction represented for African Americans and the nation. But within a decade after the Civil War, this progress toward equality began to slip away. In 1876, through election fraud and violent suppression of the Black vote, white supremacists regained control of the South Carolina government. Many of the Rollin sisters’ political allies lost their offices, including Frances Rollin’s husband, William J. Whipper.

After the death of Katherine Rollin in 1876 and their father William Rollin in 1880, the surviving sisters left South Carolina. Charlotte, Louisa, and Florence moved to Brooklyn, New York, and operated a boardinghouse. Frances Rollin Whipper moved to Washington, D.C., where she hosted a salon that attracted visitors from the city’s literary and political circles.