Visions of Freedom: Land and Labor

Establishing economic independence was crucial for newly freed African Americans during

Reconstruction. But without land of their own or fair wages for their labor, they would remain under the power of white landowners. Blocked from attaining their goals, thousands of African Americans left the South in search of better opportunities.

Black Labor During Reconstruction

Weighing Cotton, Thomas County, Georgia, ca. 1895

Newly freed African Americans sought appropriate compensation for their labor to secure economic independence and support themselves and their families. In general, white employers kept wages as low as possible, and used intimidation, fraudulent business practices, and other backhanded approaches to control and exploit freedpeople’s labor.

Sharecropping, a labor system in which families raised crops on someone else’s land and divided the harvest with the landowner, became widespread across the South after the end of slavery. Under this system, sharecroppers had to borrow on credit from landowners and local merchants at the start of the growing season to pay for rent, food, fertilizer, seed, and tools. The price sharecroppers received for selling harvested crops was often not enough to cover their debts, which kept them trapped in a cycle of poverty, under the economic control of the landowners.

The gentleman I was working with, he wanted me to work for nothing. . . . He said if I undertook to leave he would Ku-Klux me.

Warren Jones, 1872

Labor Contracts

Freedman’s Labor Contract

Family’s Labor Contract

Freedom offered African Americans the opportunity to work for themselves. But Black Codes, discriminatory laws passed by some southern states, required newly freed people to sign labor contracts with white planters on terms nearly indistinguishable from slavery. Starting in 1865, Freedmen’s Bureau agents helped with contract negotiations and sometimes required planters to agree to more fair conditions and compensation. But some agents sided with white employers, using their position to procure cheap labor for southern plantations.

Reading the Contract, Grove Plantation, Port Royal, South Carolina, 1863

Convict Leasing

Southern states created a variety of statutes, often called vagrancy laws, that made it easy to arrest African Americans for minor offenses such as loitering. Even not having a job was criminalized. Men and women convicted of such crimes could be leased by local authorities as laborers for railroads, mines, factories, plantations, and private homes.

By the 1880s, convict leasing had become an important source of labor in southern states. Dangerous working conditions often led to high death rates among workers.

The system of convict labor is nothing more or less than a system of slave labor.

William Sanders Scarborough, 1891

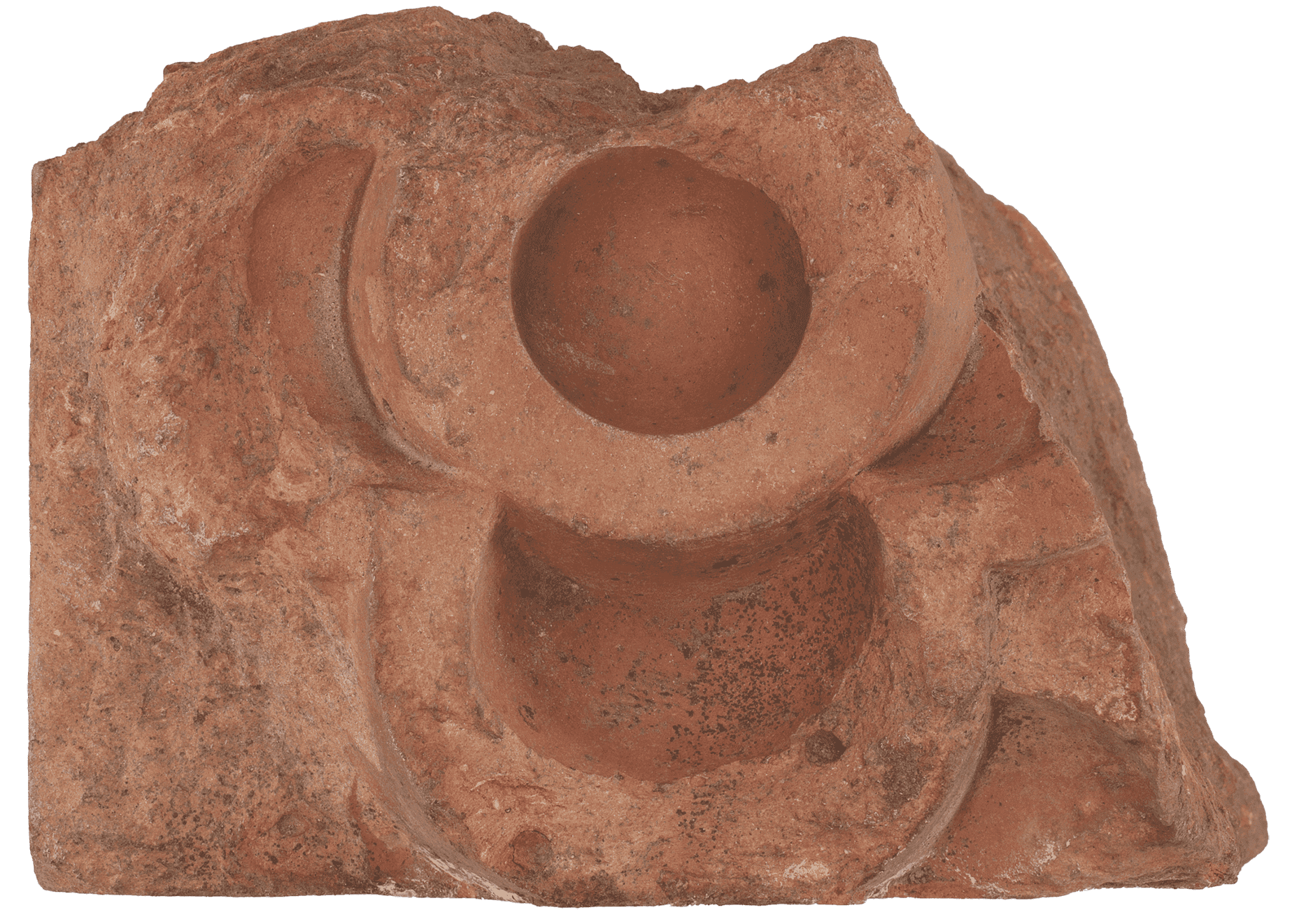

Brick from the Chattahoochee Brick Company

The Chattahoochee Brick Company was founded in Georgia around 1890 and relied on convict labor to produce bricks. Grueling working conditions resulted in high mortality among workers, many of whom were African American.

Women and Work

‘Please Settle Justly with the Colored Girl Eliza’

African American women labored both inside and outside the home. The majority of those who worked outside the home were domestic workers such as maids, washerwomen, nurses, and cooks. Many worked as farm laborers while also tending gardens to grow food for their own families. Like their male counterparts, newly freed African American women sought to control their own labor, secure fair wages and safe working conditions, and start their own businesses.

I wish to tell you if you give me twelve dollars per month I will stay with you, but if not, I have had good offers and I will find another place.

Kate, freedwoman in Georgia, to her former enslaver, 1867

The Atlanta Washerwomen’s Strike

African American women’s appeals for better wages were consistently met with resistance, though many women remained undeterred. A successful 1881 washerwoman strike in Atlanta, Georgia, resulted in higher wages for the washerwomen and other service workers.

Women Inventors

Patent drawing for dough kneader and roller invented by Judy W. Reed, 1884

Patent drawing for ironing board invented by Sarah Boone, 1892

Patent drawing for cabinet bed invented by Sarah E. Goode, 1885

African American women used their domestic knowledge and entrepreneurial skills to file for patents. Judy Reed, inventor of an improved dough kneader and roller, was the first African American woman to receive a patent. Sarah Boone, born in slavery, patented improvements for an ironing board. Sarah E. Goode, a cabinetmaker and furniture store owner, created a combination cabinet and bed designed to maximize the use of small spaces.

Harriet Tubman’s Wartime Service

Harriet Tubman, ca. 1868

Apron owned by Harriet Tubman

Harriet Tubman’s Affidavit, ca. 1898

Renowned for guiding enslaved people to freedom as a conductor on the Underground Railroad, Harriet Tubman (ca. 1822–1913) also served the US Army during the Civil War as a nurse, cook, scout, and spy. But she was not paid for most of her service. For years after the war, Tubman’s supporters lobbied the government for compensation, without success. Meanwhile, Tubman continued her humanitarian efforts, raising money for the Freedmen’s Bureau, providing care for the elderly, and advocating for women’s suffrage.

In 1895, Tubman was granted a widow’s pension for her late husband Nelson Davis, a Civil War veteran. She petitioned Congress for additional compensation, citing her own wartime service. In 1899, Congress authorized an increase in her widow’s pension, from $8 to $20 a month, but did not officially recognize Tubman’s service.