Chapter 4

Pushing for Permanent Change

African Americans, along with their allies, pushed to secure civil rights by changing America’s laws. Through large demonstrations and marches, activists brought the nation’s attention to the struggle for civil rights and full citizenship.

But some younger African Americans wanted more direct results. Frustrated by the slow, gradual change of the Civil Rights Movement, they looked to the Black Power Movement and its demands for immediate equality.

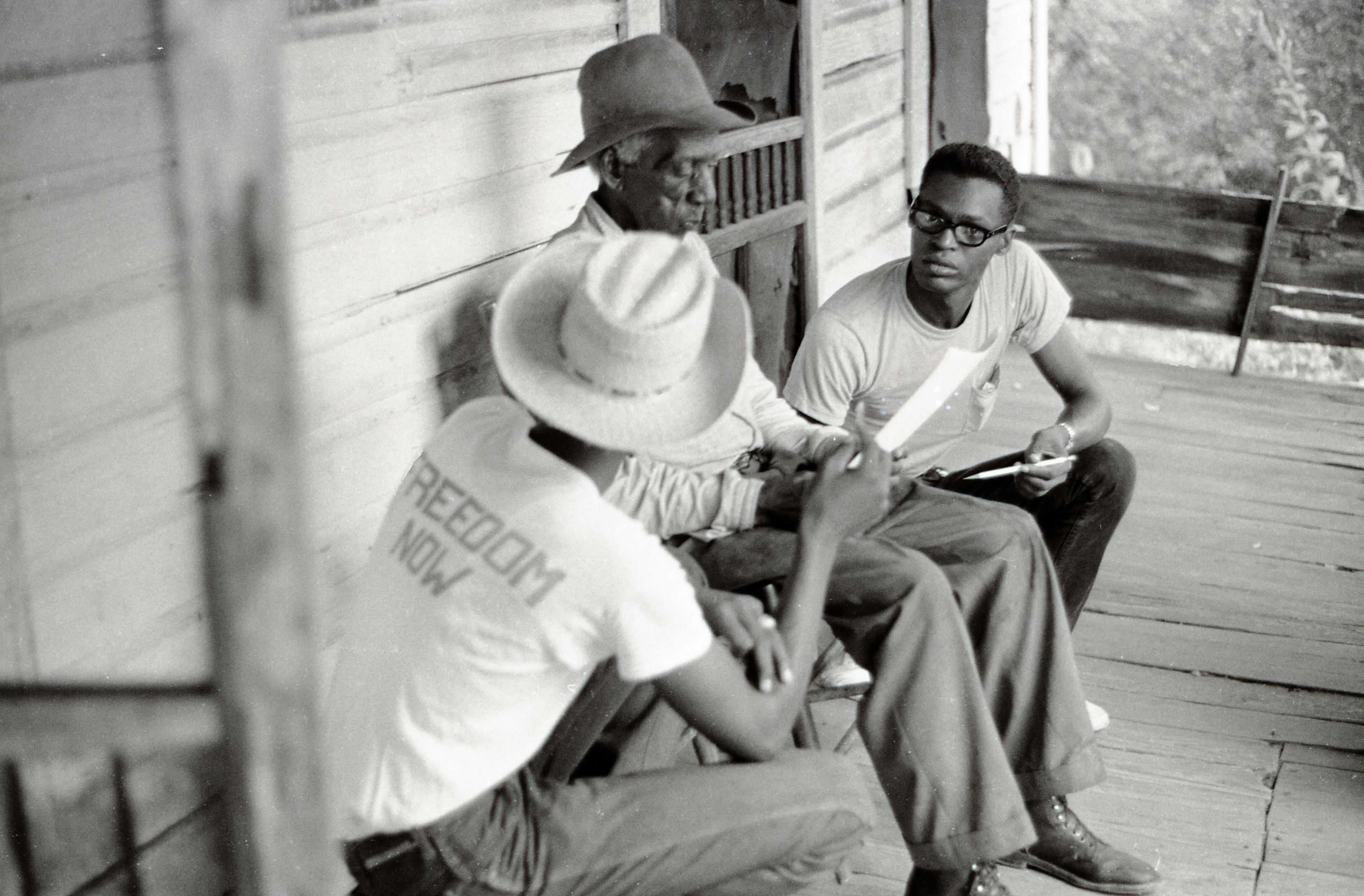

What Was Freedom Summer?

Sandra Adickes teaching in a Freedom School

In the early 1960s, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) member Bob Moses was having limited success working on voter registration in rural Mississippi. To help register Black voters and attract more national attention, Moses and his colleague Al Lowenstein, a white, Yale-educated lawyer, recruited mostly white northern college students to join them in the 1964 Mississippi Summer Project. The project, also known as Freedom Summer, founded dozens of Freedom Schools for rural students, and helped several thousand African Americans register to vote.

Fannie Lou Hamer and the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party

Fannie Lou Hamer and Ella Baker at the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party state convention in Jackson, Mississippi, 1964

Fannie Lou Hamer was one of the Civil Rights Era’s most prominent activists. Born in Montgomery County, Mississippi, Hamer began her work in 1962 as a SNCC organizer working to register African American voters. By 1964, Hamer had cofounded the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), which challenged the Democratic Party’s efforts to block Black voting in Mississippi. The MFDP was formed as part of the 1964 Mississippi Summer Project (Freedom Summer) that brought college students to help register African American voters. Hamer’s profile rose through her televised speeches, and she became a civil rights icon, running for the Mississippi House of Representatives and challenging the pro-segregation Democratic Party.

The Murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner

“The Freedom Summer Murders”

FBI photograph of the burned-out station wagon the three slain civil rights workers drove

James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner all joined the Mississippi Summer Project in 1964. But while investigating the burning of a Baptist church, they disappeared. Seven weeks later, their bodies were found buried in a dam. It was later discovered they had been arrested by local police, released, and then chased by a deputy sheriff and two carloads of Klansmen. The men shot Schwerner and Goodman, who were white, and beat Chaney, who was Black. Eighteen men were eventually tried for the murders in federal court, but only seven were convicted; the others were acquitted by the all-white jury.

KKK Resistance

KKK rally and cross burning in North Carolina during the summer of 1964

Ku Klux Klan meeting in North Carolina

The Ku Klux Klan opposed the activities of civil rights workers. Through marches, cross burnings, and violence, the Klan sought to discourage efforts like the Mississippi Summer Project. In many southern communities, local officials were members of the Klan or collaborated with them, making it difficult to arrest and prosecute offenders.