Chapter 4

Pushing for Permanent Change

African Americans, along with their allies, pushed to secure civil rights by changing America’s laws. Through large demonstrations and marches, activists brought the nation’s attention to the struggle for civil rights and full citizenship.

But some younger African Americans wanted more direct results. Frustrated by the slow, gradual change of the Civil Rights Movement, they looked to the Black Power Movement and its demands for immediate equality.

The Long Struggle to Vote

Voting rights were the key concern of the Civil Rights Movement in 1965. For all its influence, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 left many laws intact that prevented African Americans from voting.

Across the South, literacy tests, poll taxes, and other regulations discouraged voting, especially in areas with large Black populations. Activists urged Congress to pass legislation that removed these obstacles and gave African Americans the ability to exercise their rights as citizens.

Alabama poll tax payment certificate

Frances Albrier Registers Voters

Frances Albrier working with the NCNW to register voters

Registering voters has been the focus of civil rights organizations for decades. Pioneering activist Frances Albrier worked with the National Council of Negro Women in Berkeley, California, to register voters. In 1954 she received the NAACP’s Fight for Freedom Award.

Registering Voters in Selma, Alabama

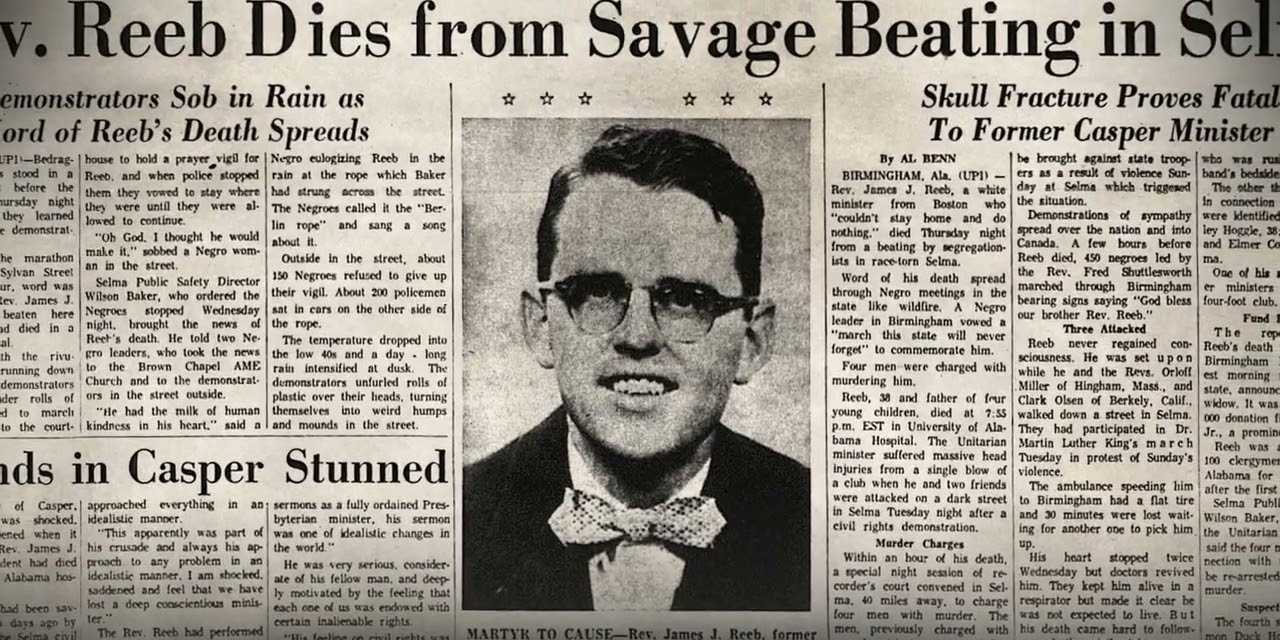

Martin Luther King Jr. launched a voter registration drive in Selma, Alabama, in 1965, but local officials resisted. Courts then ordered voter registration tests opened to African Americans, but no one passed. After a Black voting rights activist, Jimmie Lee Jackson, was killed by police in nearby Marion, King called for a march from Selma to Montgomery.

March from Selma to Montgomery

Marchers outside the Alabama state capitol in Montgomery

Martin Luther King Jr. leads marchers into Montgomery, Alabama.

In 1965, Hosea Williams of the SCLC and John Lewis of SNCC organized a march from Selma to Montgomery for voting rights in Alabama. But when 600 marchers were stopped at the Edmund Pettus Bridge outside Selma, police officers attacked. Television coverage of “Bloody Sunday,” with scenes of marchers being clubbed, whipped, and tear-gassed, outraged viewers. After a federal judge intervened, 300 marchers joined a second walk from Selma to Montgomery. The marches helped secure passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act five months later.

1965 Voting Rights Act

The passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was a victory for the Civil Rights Movement.

President Lyndon B. Johnson signs the Voting Rights Act as Martin Luther King Jr. and others look on.

President Lyndon B. Johnson introduced the Voting Rights Act to Congress in March 1965, the same month that voter registration protests began in Selma, Alabama. The violence in Alabama added pressure on Congress to act, and the bill passed in four months.

The act outlawed literacy tests, poll taxes, and other obstacles to voting. It also gave the federal government the authority to take over voter registration wherever voting rights were threatened. The act helped bring African Americans to the polls and helped African Americans reach elected office.

Impact of the Voting Rights Act

NAACP Secretary Roy Wilkins meets with President Lyndon B. Johnson to discuss how to pass the Voting Rights Act.

The 1965 Voting Rights Act improved voter participation in places where access had long been denied to African Americans. The act removed barriers to voting and allowed federal officials to monitor voting procedures.

The act also led to the election of more African Americans to local and national offices. For instance, in Georgia, eight African Americans were elected to the State House of Representatives in 1966. Though the act did not fully end voting discrimination, it gave government officials more power to address discrimination once identified.

John Lewis

The Unending Struggle

John Lewis at the March on Washington

By age 25, John Lewis was a veteran of the Civil Rights Movement. He had taken part in sit-ins, Freedom Rides, voter registration drives, and the March on Washington. The national chairman of SNCC, he had been arrested and jailed, and was nearly beaten to death on “Bloody Sunday”—the first Selma to Montgomery March.

In 1981, Lewis was elected to the Atlanta City Council, and in 1986, he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. He continued to advocate for human rights and served in Congress until his death in 2020.