Chapter 4

Pushing for Permanent Change

African Americans, along with their allies, pushed to secure civil rights by changing America’s laws. Through large demonstrations and marches, activists brought the nation’s attention to the struggle for civil rights and full citizenship.

But some younger African Americans wanted more direct results. Frustrated by the slow, gradual change of the Civil Rights Movement, they looked to the Black Power Movement and its demands for immediate equality.

“Bombingham”

In 1963 Martin Luther King Jr. called Birmingham, Alabama, “the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States.” As civil rights activists won battles to outlaw segregated public facilities, Birmingham chose to close its parks and swimming pools rather than integrate them. White segregationists also used violence to intimidate African Americans who demanded change.

Ku Klux Klan (KKK) members held office in Birmingham’s local government, and Birmingham’s Commissioner of Public Safety, Theophilus Eugene “Bull” Connor, was infamous for his willingness to use violence against civil rights demonstrators. African Americans’ homes and churches were targeted by terrorists. During the 1950s and 1960s alone there were more than 50 unsolved bombings in Birmingham.

The SCLC’s Birmingham Campaign

Henry Shambry is attacked by police dogs during a demonstration in Birmingham, Alabama.

Commissioner Bull Connor ordered the use of high-pressure water hoses on Birmingham marchers.

To maintain momentum within the Civil Rights Movement, Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) planned a major campaign in Birmingham, Alabama. The operation began in April 1963 with sit-ins and marches demanding desegregation and jobs for African Americans. Local police, under the authority of Public Safety Commissioner Bull Connor, responded with police dogs and fire hoses. The images of peaceful protesters assaulted by Birmingham police led to national outrage. By May, an agreement was reached to integrate downtown facilities and hire more Black employees in Birmingham.

Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, Civil Rights Leader

The bombed home of Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth next to his church, Bethel Baptist

Fred Shuttlesworth believed faith sustained him through the many beatings and arrests he endured.

A Baptist minister, Fred Shuttlesworth helped found the SCLC and was an opponent of segregation in Birmingham, Alabama. He survived a bombing at his home on Christmas Day 1956. In 1957, he and his wife were beaten when they tried to integrate their daughter into a white school. Undeterred, Shuttlesworth provided shelter for Freedom Riders, invited Martin Luther King Jr. to Birmingham in 1963, and helped organize the Selma to Montgomery March in 1965. His bravery made him one of the most respected civil rights leaders in America.

The Bombing of 16th Street Baptist Church

16th Street Baptist Church after the bombing

Sixteenth Street Baptist Church was a neighborhood church for hundreds of people who attended church services or gathered in its basement for Sunday school. Many civil rights marches in Birmingham began at the steps of the church.

On Sunday, September 15, 1963, the Ku Klux Klan bombed 16th Street Baptist Church. The explosion was the third bombing in 11 days, after a court-ordered desegregation of Birmingham schools.

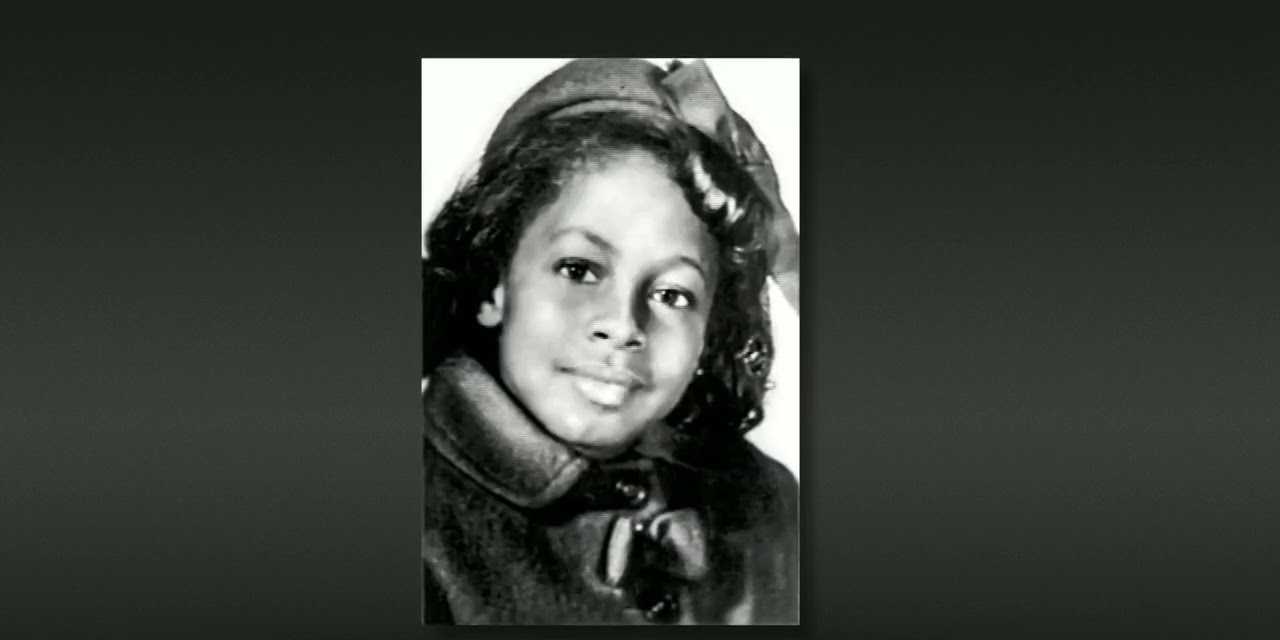

As the building filled with smoke, its occupants rushed outside, injured and shaken. Four young girls—Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair, Carole Robertson, and Cynthia Wesley—who were in the church basement when the bomb exploded were killed.

“The Day a Church Became a Tomb”

Ten shards of stained glass from 16th Street Baptist Church

When the dynamite exploded, it blew a hole in the church's rear wall and shattered all but one stained-glass window. The bodies of four young girls were found in the rubble. A fifth girl survived but lost an eye. The girls’ deaths shocked the nation, and more than 8,000 mourners attended their funeral.

The four girls killed in the bombing of 16th Street Baptist Church, clockwise from top left: Denise McNair, 11; Carole Robertson, 14; Addie Mae Collins, 14; and Cynthia Wesley, 14.